The First heart failure drug geared specifically to blacks not only improves

survival and reduces hospitalization rates among patients, but also results in

cost savings.

survival and reduces hospitalization rates among patients, but also results in

cost savings.

“Doctors should probably give BiDil to blacks with grade III heart failure,

and they should probably do it even if these patients are relatively

well-managed on existing medications,” said Dr. Derek C. Angus, lead author of a

study in the Dec. 13 issue of Circulation.

“The data is important,” added Dr. Hector Ventura, head of the cardiomyopathy

and heart transplantation center at the Ochsner Clinic Foundation in New

Orleans. “Whether or not other medicines work, at least we’re focusing on the

population that needs it.”

Heart failure, a condition in which the heart loses its ability to pump,

affects about 5 million Americans, including an estimated 750,000 blacks. And

blacks aged 45 to 64 are two-and-a-half times more likely to die from heart

failure than whites of similar age.

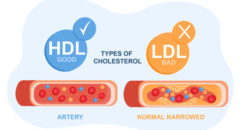

The discovery of BiDil as an effective heart failure therapy for blacks was

an accident. It is actually a combination of two older drugs — hydralazine, an

anti-hypertensive agent that relaxes the arteries, and isosorbide dinitrate, an

anti-anginal agent that relaxes the veins and arteries. Neither drug was

approved for heart failure before clinical trials began, and it is still unclear

how the two work together.

In an earlier trial, BiDil did not have much effect in white patients but did

do well among black patients.

That trial was the impetus for the African-American Heart Failure Trial

(A-HeFT), designed to look specifically at the effects of BiDil in more than

1,000 black heart patients.

A-HeFT found a 43 percent reduced risk of death (6.2 percent vs. 10.2

percent), 39 percent reduced risk of first hospitalization and improved quality

of life among participants taking BiDil plus standard heart failure therapies

when compared to those taking only standard therapies. Indeed, the results were

so encouraging that the trial was halted early, in July 2004.

The current study is based on A-HeFT data, this time focusing on resource

use, costs of care and cost-effectiveness within the same trial population. The

study was funded by NitroMed Inc., which makes BiDil.

Individuals treated with BiDil had 30 percent fewer hospitalizations and

shorter hospital stays (one day shorter) compared with the placebo group. This

resulted in a 41 percent reduction in the number of days spent in the hospital

for heart failure.

In the BiDil group, heart failure-related costs averaged $5,997 — 34 percent

lower than the $9,144 seen in the placebo group.

Total health-care costs averaged $15,384 in the BiDil group, which was 22

percent lower than the average of $19,728 in the placebo group.

The authors projected that, by using BiDil, heart failure-related costs would

be $16,000 a year at two years after starting the drug.

With an average daily cost of $6.38, BiDil has been the subject of some

controversy. If the two drugs were taken separately, the cost would be only

pennies per day. This particular combination, however, has been patented and

likely results in better patient compliance because it is one pill, not two.

According to this study, that extra cost is being more than made up for in

reduced overall health-care costs.

“Regardless of what you think of the pricing policy, it’s actually a cost

savings, at least over the duration of the study period,” said Angus, professor

of critical care medicine and health policy and management at the University of

Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “Six dollars a day is keeping the doctor away.

It’s decreasing the likelihood of acute hospitalization. One might think it’s

more than 60 cents, but it’s a lot less than being hospitalized.”

More information

The National Minority Health Month has more on

heart failure in blacks.

SOURCES: Derek C. Angus, M.D., professor, critical care medicine and

health policy and management, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine;

Hector Ventura, M.D., head, cardiomyopathy and heart transplantation center,

Ochsner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans; Dec. 13, 2005, Circulation

Copyright © 2005 ScoutNews, LLC. All rights reserved.