We started out a couple of articles ago with the theme of HIV as a party virus. By this, we mean that HIV likes to hang out with all sorts of other disease-causing viruses, bacteria and other organisms.

Because HIV is sexually-transmitted, we should not be surprised that HIV patients often have other sexually transmitted infections. But sometimes, the relationships are even greater. This means that while we are managing HIV, we also have to be checking to see if any of its “friends” have come along for the “party” so we can deal with them appropriately. HIV’s friends can cause many problems, for example, we have discussed how Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C viruses can cause cirrhosis and liver cancer: bad news!

What is HPV?

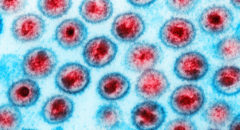

One of HIV’s favorite party companions is the Human Papilloma Virus, often abbreviated HPV. There are lots of different strains of HPV and they are commonly found in both men and women. Most strains of HPV don’t cause any serious problems, but a few strains do cause disease. A couple strains are known to be responsible for causing cervical cancer and also cancer of the anus. A couple of different strains cause genital warts. Genital warts look like crusty clusters that can appear on the penis, the labia, vulva or anus.

Sometimes they can get quite large looking like miniature clusters of grapes, or even having a cauliflower-like appearance. Not surprisingly, this virus that causes problems in the anal/genital area is mainly sexually transmitted. It also may be the cause of other types of cancers in different parts of the body.

When HIV and HPV party together, this usually means trouble. Since both viruses are sexually transmitted, they are commonly found together. But because HIV impairs the immune system, the body can’t fight off the dangerous strains of HPV as easily. So while cervical cancer, anal cancer and genital warts occur in the general population, they are all more common in HIV infected persons, and often are worse in persons with advanced HIV disease.

Screening

There is a test that can detect whether a person is infected with HPV and whether than strain is dangerous or not. Your doctor can do this test.

Cervical cancer

Early in the HIV epidemic in the US (1980’s) we didn’t know a lot about how HIV affected women. Most cancers take years to develop, and since there weren’t effective treatments for HIV, people died from HIV before cancers could develop.

Also, many doctors only viewed HIV as a disease of white gay men and simply weren’t looking for HIV infection in women, especially black women. It took quite a while for the link between HIV infection and cervical cancer to be worked out, and many women likely died of cervical cancer without ever knowing they were HIV-infected. In 1993, the presence of cervical cancer in a woman with HIV-infection was considered a diagnosis of AIDS, the advanced stage of HIV-infection.

Years ago, a procedure was developed designed to detect cervical cancer early so that it could be treated before progressing to a more dangerous form of cancer. This test, called a Pap smear involves collecting cells from the opening of the cervix using a special swab. The cells are spread onto a slide and viewed under a microscope by a technician or medical provider trained to recognize abnormal cells. If abnormal cells are detected, this could be a sign that there are changes taking place in the cervix that could lead to cancer. A medical provider can then view the cervix using a special instrument (a colposcope) to see if there are cancerous areas, and then treat them. By having regular Pap smears in women, medical providers could detect cancers early and treat them. This procedure has saved millions of women’s lives and proven to be an effective screening method.

Screening in HIV-infected patients

Because HIV changes the immune system, cancer could develop earlier and more aggressively than in women without HIV-infection. Women newly diagnosed with HIV should receive a Pap smear soon after the diagnosis and then, about 6 months later. After the first year, they should receive a pap smear every year.

Anal cancers

In the general population, anal cancers can affect both men and women, but are not particularly common. All individuals with HIV infection are at increased risk of anal cancer from HPV, but it occurs more frequently in men who have sex with men (MSM) than in women or heterosexual men with HIV. Just as a Pap smear can detect changes in the cervix that could be cancerous, a pap smear can also detect cancerous cells from the anus, and if caught early, treatment can be initiated. Unfortunately, anal Pap smears are not frequently done, and sadly, many medical providers have never even heard about them. All HIV-infected patients should receive anal Pap smear screening regardless of the gender or sexual orientation, but MSM’s should be more proactive in seeking this important screening. Doctors who specialize in HIV care are more likely to be able to provide this service or refer you to a trained clinician.

Prevention

The use of condoms has been shown to reduce HPV transmission just as it reduces transmission of HIV. One major concern is that genital warts can transmit the HPV virus to another person through contact with the skin. This is important to keep in mind because genital warts may occur on parts of the genitalia not covered by a condom and could make contact with the partners skin.

A few years ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first HPV vaccine. As I mentioned earlier, there are many strains of HPV. The vaccine was specifically designed against the strains that cause cervical and anal cancer. The vaccine works by teaching the immune system to eliminate the dangerous strains of HPV; the ones that cause cervical and anal cancer. Since HPV is sexually transmitted, it was important to have them vaccinated before they became sexually active.

They would then be protected if exposed to one of the cancerous strains. The vaccine, named Gardisil, was approved for use in girls. Vaccinating women and girls is a good strategy to protect them from cervical cancer (and anal cancer). But recall that HPV infects both men and women. So recently, the FDA approved Gardisil for boys as well. If men are protected against the cancerous forms of HPV, they won’t be able to infect women with these strains. So we can target cervical cancer on two fronts by vaccinating men and women.

A couple of recent studies clearly show the benefit of the HPV vaccines in protecting women from cervical cancer, but the protective effect was much higher in women who were younger when they received the vaccine.

In a recent study, a group of gay men who received the HPV vaccine had significantly lower cases of the early forms of anal cancer compared to men who didn’t get vaccinated. The men who received the vaccine were less likely to have the cancerous forms of HPV detected in their tissues.

Studies are in progress to determine if HPV vaccines can offer protection in HIV-infected people against cervical and anal cancer. Having a strong immune system from taking HIV medicines may be an important factor in making the HPV vaccine effective.

CHECK: HPV: The Not-So-Silent STD

Treatment

There are several options of treatment for genital warts that can remove them and reduce there chance of infecting someone else. Some of these include Podophyllin, Tricloroacetic acid and cryotherapy.

There are also treatment options for cervical cancer and anal cancer that can be effective if the cancers are detected early. Regular screening is the best way to detect any cancers developing while they are still responsive to drug treatment or surgical procedures.

Treatment of HIV infection improves the immune system and builds it up to help fight cancers. Some of these cancers may occur less frequently in HIV patients with strong immune systems.

There are a few drugs that can suppress HPV but they are not typically used in medical practice because most strains of HPV are not dangerous. When cancers are detected early, they can often be cured.

READ: HPV Vaccine More Effective In Reducing Cancer Cell Growth Than Experts Expected

Dr. Crawford received a B.S degree in Biology from Cornell University and a B.S. in Pharmacy from Temple University. He completed a residency in clinical pharmacy at the National Institutes of Health. He earned a doctorate in Pharmacology from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. He completed a post-doctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, studying microbial biochemistry and genetics.

Dr. Crawford received a B.S degree in Biology from Cornell University and a B.S. in Pharmacy from Temple University. He completed a residency in clinical pharmacy at the National Institutes of Health. He earned a doctorate in Pharmacology from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. He completed a post-doctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, studying microbial biochemistry and genetics.

He is currently with the Division of AIDS at the National Institutes of Health. He has over 25 years of experience in HIV treatment and clinical research. This article reflects his personal views and opinions.