a simple procedure, says Theresa Giambra, who was director of the Cardiac Rhythm Device Clinic in Buffalo, New York, at the time and overseeing Mathews’ care.

“It truly isn’t a huge surgery,” Giambra shares. “Often patients go home within 24 hours.”

But Mathews didn’t go home that day, or even the next one. When she was given fentanyl to dull the pain of the surgery, her heart stopped. She wound up in a coma, awaking more than a week later in a horrifying state of confusion.

“I remembered my mother and my children, but nobody else,” she says.

Unsure what was happening to her, she fought with the nurses and ripped out her breathing tube, injuring her vocal cords.

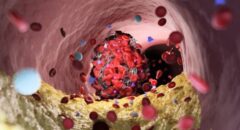

When her head finally cleared, she had another shock: While she’d been in a coma, her family gave doctors permission to implant a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, in her chest. It’s a drastic step done when a heart can’t properly pump blood on its own, often used as a way to keep someone alive until they can get a heart transplant, or as an alternative treatment when someone isn’t eligible for a transplant.

Mathews knew she was a candidate for the device but didn’t want one because the cumbersome apparatus would restrict daily activities and be difficult to hide. And Mathews, who enjoyed wearing cute outfits and going out dancing, didn’t want to be permanently tied to all that equipment.

“It was vanity. It’s scary when you see it,” she adds. “And I didn’t want a hole in my stomach.”

When she got home from the hospital, Mathews had to rely on others. She became frustrated and depressed and refused to leave the house.

“Usually, I’m the fixer,” she notes. “I fix everything for everybody else, but I couldn’t fix this for me.”

Regaining her independence

A physical therapist who came to the house pushed her to recover her health and her ability to