Health history is likely not something you think about on a regular basis. You might consider it once a year when visiting a healthcare provider. You flip through the required pre-appointment paperwork, answer what you can, the information gets filed away, and you go on with your routine visit. But our family’s health history can be a key indicator of our own health risks.

If we have breast cancer in our family, especially in a mother, sister, or grandmother, we can’t let this critical piece of information get lost in our patient files. That knowledge can be incredibly powerful in determining our own breast cancer risk. And as black women, we’re facing a greater risk of mortality from breast cancer than white women. Prevention is paramount and has the power to change those odds.

The State of Breast Cancer in Black Women

The rates of black women diagnosed with breast cancer are comparable to other races, and yet women are disproportionately dying of the disease despite its generally high survivability (when detected early, the 5-year survival rate for breast cancer can be greater than 98%).

Between 2010 and 2014, black women were dying of breast cancer at a rate 43% greater than white women. In Memphis, the odds of black women dying of breast cancer are double that of white women. In Chicago, recent strides have been made to reduce the gap from 62% to 39%, but the significant disparity still remains.

There are many reasons for these disparities, some of which are beyond our control. But by understanding the issue and our own personal risk, we can be empowered to manage our breast health proactively.

A Family Matter

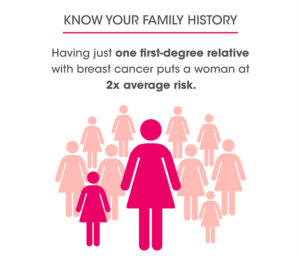

1 in 8 women, or 12% of women in the country, will be diagnosed with breast cancer. However, if you have a first-degree relative (a mother, a sister, or a grandmother) who was diagnosed with breast cancer, your personal risk automatically doubles.

It becomes even greater if that family risk is coming from a genetic mutation, meaning a fault in one of the genes in your body charged with protecting you from cancer. While rates of genetic mutations are relatively low, black women are more likely to have a BRCA2 mutation, which can increase your risk of getting breast cancer to up to 84%.

That’s why it’s so important to ask your family questions about their medical history. It can be difficult (sometimes impossible) and uncomfortable, but if