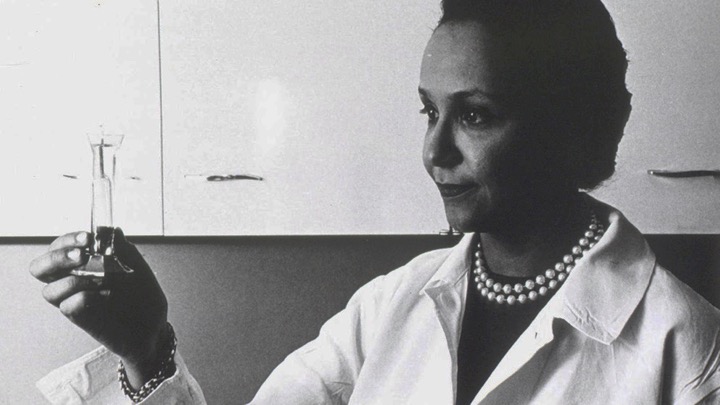

A major breakthrough in cancer treatment was the development of chemotherapy in the 1940s. The first chemical noted for its anti-cancer effects were nitrogen mustards. Dr. Jane Cooke Wright played a fundamental role in this story. During her career she would break multiple race and gender barriers and become one of the most distinguished physician-scientists in modern medicine. In fact, her work revolutionized cancer research and how physicians treat cancer.

A major breakthrough in cancer treatment was the development of chemotherapy in the 1940s. The first chemical noted for its anti-cancer effects were nitrogen mustards. Dr. Jane Cooke Wright played a fundamental role in this story. During her career she would break multiple race and gender barriers and become one of the most distinguished physician-scientists in modern medicine. In fact, her work revolutionized cancer research and how physicians treat cancer.

Born in New York City in 1919, Jane Cooke Wright was the first of two daughters born to Corrine (Cooke) and Louis Tompkins Wright. Her father was one of the first African American graduates of Harvard Medical School, and he set a high standard for his daughters. Dr. Louis Wright was the first African American doctor appointed to a staff position at a municipal hospital in New York City and, in 1929, became the city's first African American police surgeon. He also established the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital.

Jane Wright graduated with honors from New York Medical College in 1945. She interned at Bellevue Hospital from 1945 to 1946, serving nine months as an assistant resident in internal medicine.

In January 1949, Dr. Wright was hired as a staff physician with the New York City Public Schools, and continued as a visiting physician at Harlem Hospital. After six months she left the school position to join her father, director of the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital.

Chemotherapy was still mostly experimental at that time. At Harlem Hospital her father had already re-directed the focus of foundation research to investigating anti-cancer chemicals. Dr. Louis Wright worked in the lab and Dr. Jane Wright would perform the patient trials. In 1949, the two began testing a new chemical on human leukemias and cancers of the lymphatic system. Several patients who participated in the trials had remission and they knew they were on to something.

In 1952, following her father’s death, Dr. Jane Wright was appointed the director of the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital. In 1955 she became an associate professor of surgical research and director of cancer chemotherapy research at New York University Medical Center, and she turned her research program towards personalized medicine. Wright pioneered efforts in utilizing patient tumor biopsies for drug testing, to help select drugs that may work specifically against a particular tumor. In these experiments, a small piece of the tumor was excised surgically and cultured in the laboratory. Once these cells were coaxed to grow, an arduous process in the 1950s, tumor cells were treated with different drugs in culture to help predict which drugs may produce the most robust effect in the actual patient. This is another revolutionary idea from Dr. Wright, which underlies the contemporary concept of precision medicine.

While pursuing private research at the New York Medical College, she implemented a new comprehensive program to study stroke, heart disease, and cancer, and created another program to instruct doctors in chemotherapy.

Dr. Wright led groups of oncologists to China, the former Soviet Union, Africa, and Eastern Europe to treat cancer patients. This work spanned her entire career, as her first publication about these journeys was in 1957 following her visit to treat cancer patients in Ghana.

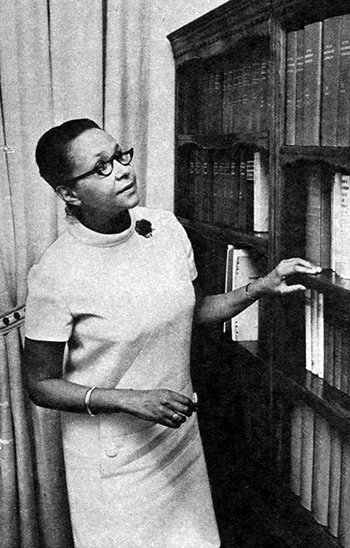

In addition to research and clinical work, Wright was professionally active. In 1964, she was one of seven founders of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and in 1971, she was the first woman elected president...

... of the New York Cancer Society. Wright was appointed associated dean and head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department at New York Medical College in 1967, apparently the highest ranked African American physician at a prominent medical college at the time, and certainly the highest ranked African American woman physician. She was appointed to the National Cancer Advisory Board (also known as the National Cancer Advisory Council) by US President Lyndon Johnson, serving from 1966 to 1970 and the President's Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke (1964–65). Wright was also internationally active, leading delegations of oncologists to China and the Soviet Union, and countries in Africa and Eastern Europe. She worked in Ghana in 1957 and in Kenya in 1961, treating cancer patients. From 1973 to 1984 she served as vice president of the African Research and Medical Foundation.

Wright was the recipient of many awards, including the honorary Doctor of Medical Sciences degree from the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania.

Wright retired in 1985 and was appointed emerita professor at New York Medical College in 1987.