The 23rd International AIDS Conference, originally scheduled for San Francisco/Oakland in late July was held virtually in early July 2020 (Yuck! I’m getting sick of virtual conferences!). Among the very interesting scientific and medical developments presented was the case of a possible cure coming out of Federal University of Sao Paulo in Brazil, presented by Diaz and colleagues.

There are many very powerful combinations of HIV drugs that suppress the replication of the virus so low that no virus can be detected in the blood. However, even after many years of being undetectable, when the person stops taking the medicine, the virus “magically” appears in the blood as it comes out of hiding. So let's quickly review why the suppression of the virus from HIV treatment doesn’t totally cure or get rid of the infection like the drugs do for an infection like Hepatitis C (see my article dated Jan 2020, “Why we haven’t cured HIV infection….”).

I should also note that there have been some unique cases where individuals have been cured, as I reported last year (posted April 15, 2019, “Could there be a real cure for HIV?”). So again I ask, could there be a real cure for HIV?

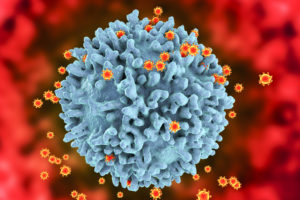

Recall that when the HIV virus infects a cell of the immune systems (white blood cells known as T-lymphocytes or T-cells), the T-cell is usually revved up and active and the virus turns the cell into a factory to make more viruses. Then the cell dies and the virus spreads to other cells. But this doesn’t happen in all T-cells.

In some special types, after the virus gets in, instead of making more virus, the infecting virus just chills out as the infected cell quiets down. So the virus is essentially sleeping inside the infected cell and not doing anything. In the quiet state, called a latently infected cell, HIV drugs don’t work well to eliminate the virus and the immune system doesn’t realize that the cell is infected.

One of the strategies to cure the infection is to basically stimulate these latently infected cells, forcing them to wake up and make virus. When that is done, there are strong combinations of HIV drugs around to get into the cell and prevent the virus from spreading, but there are also drugs to boost the ability of the immune system to kill these latently infected cells, that are now “awake”.

Eventually, all these latently infected cells would be eliminated and there would be no source of virus in a patient suppressed on therapy.

So this case involves a 35-year old Caucasian Brazilian man who came into care and was treated with the standard treatment that most people were receiving at that time for HIV (Efavirenz, tenofovir and 3TC combined into a single tablet, similar to Atripla in the US). Everything went fine with the treatment; the patient tolerated the medicines with no side effects and he was soon totally suppressed (undetectable).

So now, after two years being undetectable, additional medicines were added. The HIV treatment was intensified by adding two additional powerful drugs, dolutegravir and maraviroc (recall that he was already undetectable). Then another treatment was added called nicotinamide.

Nicotinamide is a form of the vitamin niacin (vitamin B3). So why all these extras? In addition to providing more powerful treatment against HIV, both the nicotinamide and the maraviroc are believed to stimulate these latently infected cells we mentioned earlier, forcing them to

produce HIV and to come out of hiding. It is also thought that the nicotinamide may be able to activate cells in the immune system that specialize in killing HIV infected cells. He received the experimental treatments for a year and then continued on standard therapy for another two years, and then stopped all therapy.

The first hint that this experiment was effective is that after the patient stopped taking medicine, his virus remained undetectable. As we mentioned above, in most people suppressed on therapy, virus reappears in the blood after the medicines are stopped. Not in this case. Other tests showed the presence of virus in latently infected cells declined throughout the treatment and could not be detected after treatment was stopped. This is what you would expect to find in a person with no virus in the blood after stopping their medicine. Also, the amount of circulating HIV antibodies in the blood gradually decreased over the course of the study treatment. But what is unique in this case is that the HIV antibodies remained very low after the patient stopped taking medicines, indicating very little or no virus around to stimulate antibody production.

At the time that this case was presented at the conference in early July, the patient had been off all medicines for over 64 weeks with no virus detected in the blood or anywhere else. So the key questions now are, can this patient remain “virus free”? In other words, is he truly cured? Importantly, can other patients get the same benefit from this approach? Time will tell. Stay tuned!