August 3rd was supposed to be a celebration—Abraham Kirwa’s birthday. A respected public servant and radio host in Kenya, he was preparing for an interview when he suddenly noticed his vision blurring. Moments later, he tried to sip water, but vomited everything he’d eaten that day. At 54, Abraham never imagined he’d come close to losing his life to a stroke, and especially not on the air.

“I called my wife,” he tells BlackDoctor.org. “She brought water, but I couldn’t see it. I knew something was seriously wrong.”

His wife, Frasiah Kirwa, suspected he was having a stroke and took swift action, searching for aspirin despite limited drug access in Kenya and rushing him to the hospital. Despite arriving within the critical four-hour treatment window, doctors did not administer tPA (tissue plasminogen activator), which works by dissolving the blood clot, restoring blood flow to the affected area of the brain and potentially limiting brain damage. The consequences were severe.

A Medical Crisis Across Borders

Abraham’s medical crisis would ultimately include two strokes and a diagnosis of congestive heart failure. He spent 18 days in a Kenyan hospital, during which his heart function plummeted from 25% to as low as 15–18%. With his condition worsening and treatment options limited, his wife arranged for a high-stakes emergency airlift to Dubai—a logistical and bureaucratic marathon.

At King’s College Hospital in Dubai, doctors finally dissolved a dangerous clot and stabilized his heart function to 30%. From there, Abraham was advised to continue rehabilitation in the U.S.

Texas Rehabilitation: Progress Over Perfection

Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Allen became the cornerstone of Abraham’s comeback. Once stable, his neurologist referred him to a neurological rehabilitation program focused on restoring physical and cognitive function. He began five hours of therapy a day—speech, physical, occupational, and cardiac.

“When he first came to us, he was hesitant in speech, struggling to find words and put his thoughts together. By the end, he spoke fluently—you wouldn’t even know he had suffered a stroke,” Lisa Heath, MS/CCC-SLP, speech-language pathologist at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Allen, shares.

“He practiced relentlessly—reading aloud, holding conversations, training his brain and body every day,” Heath adds.

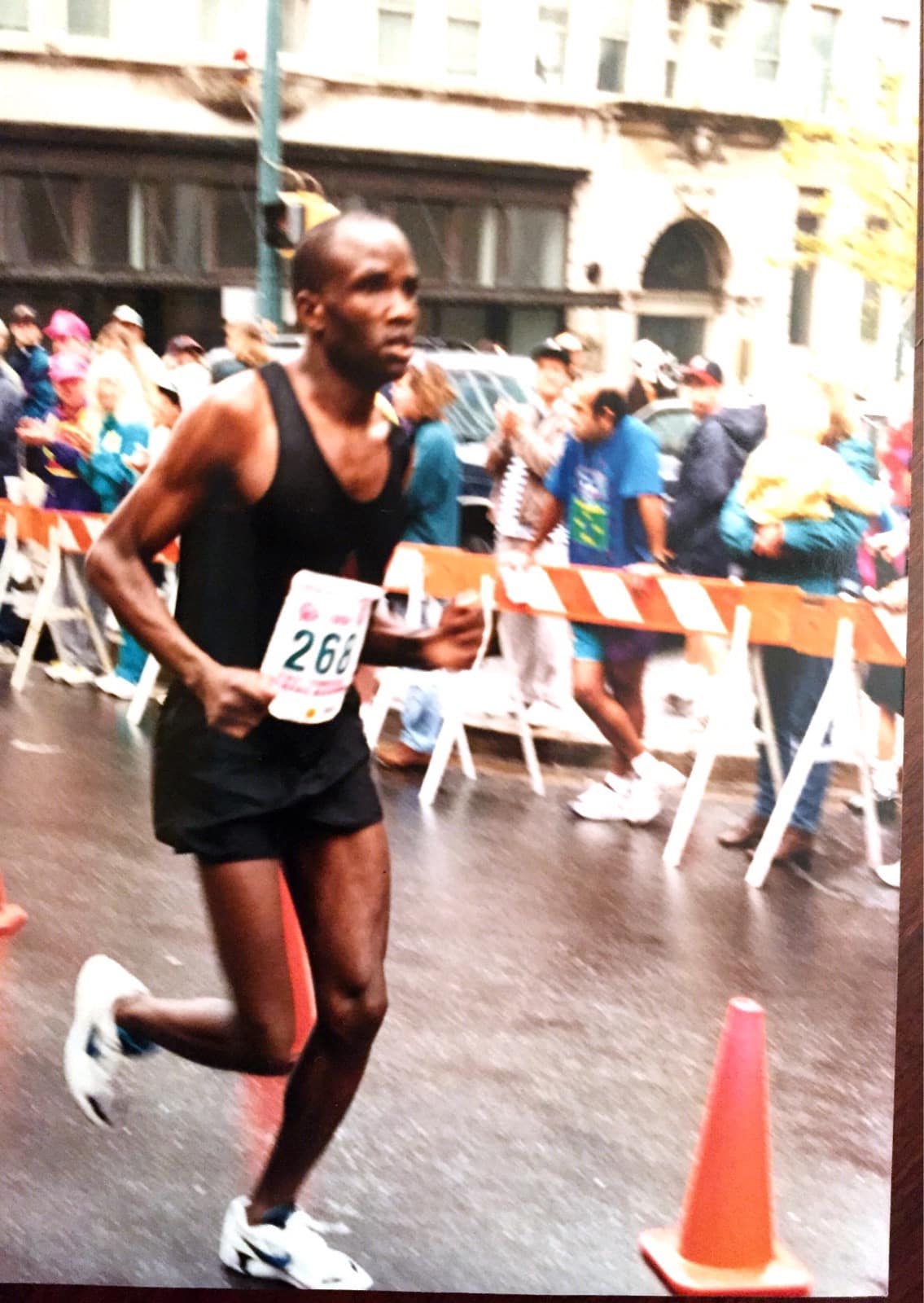

Abraham also worked with Bryan Anderson, PT, DPT, CSRS, a certified stroke rehab specialist. When Kirwa started therapy, he had a severe facial droop, difficulty speaking, poor balance, and relied on a cane. A former college long-distance runner, he was told he might never walk unaided again.

Anderson took that as a challenge. They incorporated jogging, hopping, and movement across different surfaces into the rehab program, and reminded Abraham to focus on progression, not perfection.

Over 12 weeks, he rebuilt strength and coordination through:

- Physical therapy for balance, strength, and mobility

- Occupational therapy for flexibility and daily task performance

- Speech therapy to address swallowing and communication

The Bigger Picture: Stroke Awareness and Global Gaps

Each year, more than 13 million people suffer strokes worldwide. In the U.S., around 795,000 cases occur annually. The World Health Organization notes that access to stroke rehabilitation is severely limited in many parts of the world, not just due to geography, but because of a lack of trained professionals and essential medical equipment.

“There’s a saying—‘time is brain.’ Within three hours of symptoms, a patient can receive medication that often prevents permanent disability. But you must act fast,” Heath explains.

Key symptoms include:

- Sudden numbness or weakness on one side

- Slurred or hesitant speech

- Vision loss

- Dizziness or imbalance

- Facial drooping

“If someone shows any of these signs, don’t wait. Go to the ER immediately,” Heath warns.

Top risk factors include:

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Poor diet and lack of exercise

- Diabetes

- Atrial fibrillation

- Family history

Heath emphasizes that physicians not only treat the stroke but also work preventively—through medication, cardiac evaluations, lifestyle coaching, and follow-ups to avoid recurrence.

A Caregiver’s War—and a Lawmaker’s Resolve

Throughout the ordeal, Frasiah was his fiercest advocate. She navigated Kenya’s strained health system, battled for access to care, and refused to let delays determine his outcome.

“The difference in care was striking,” she says. “In Dubai and Texas, doctors listened. They explained. They worked with us. In Kenya, we were dismissed repeatedly.”

Now, both Abraham and Frasiah are calling on leaders to bring quality stroke care to underserved communities. He knows firsthand how limited the resources are in his home country, especially in rural areas.

From Survivor to Advocate

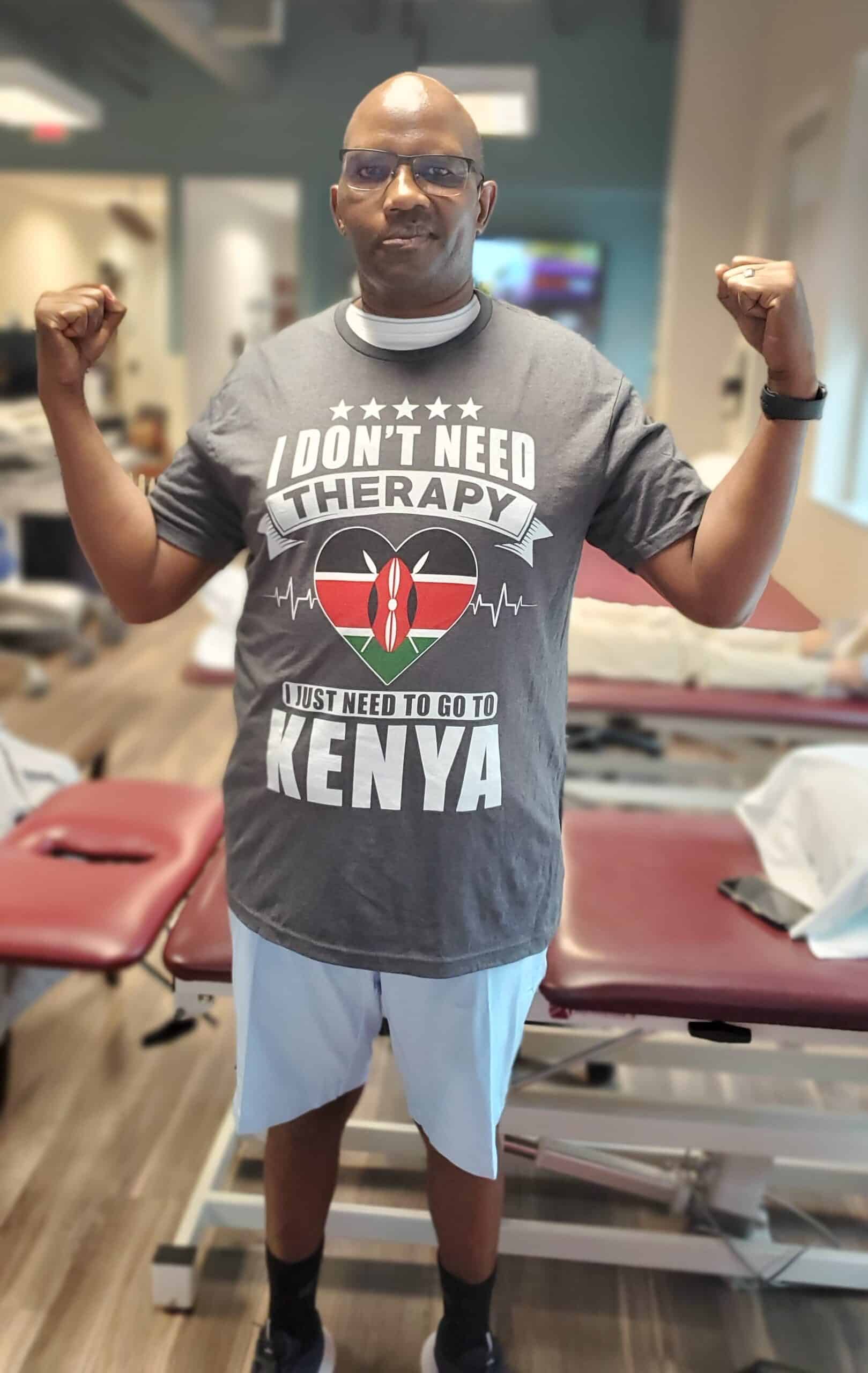

Today, Abraham walks without a cane. He talks, laughs, and runs—defying expectations. He has returned to public service as a member of Parliament, representing over 200,000 residents in Kenya’s Nandi County.

“I tell men—especially Black men and busy professionals—your health is your greatest wealth. Listen to your body. Get checkups. If you lose your health, you lose everything,” he shares.

“Growing old is a gift. Don’t take it for granted. Don’t wait to invest in your health,” he adds.

Two visiting Kenyan officials watched him speak fluently during therapy—even in his native dialect—and were stunned. It’s become his mission to bring integrated rehab programs like Texas Health’s back home.

His message to fellow survivors?

“Your body is your temple. If you take care of it, it will take care of you. Walk. Eat well. Exercise. Heal.”

And his message to policymakers?

“Health systems must be built for everyone, not just the fortunate,” he concludes.