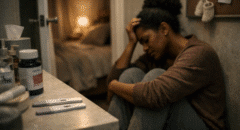

The words “calm down” are worse than unhelpful—they can actually increase blood pressure among new mothers of color, a study has found.

Gender-based racism, expressed through microaggressions, significantly increased blood pressure in new mothers compared to women not subjected to such comments, researchers reported in a study published January 9 in the journal Hypertension. These effects were even more pronounced among women living in areas with high levels of structural racism.

“It is well-known that Black, Hispanic, and South Asian women experience microaggressions during health care. It is not as well known whether these microaggressions may have an association with higher blood pressure,” said lead researcher Teresa Janevic, an associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, in a news release.

For the study, researchers asked nearly 400 women of color who gave birth at four hospitals in Philadelphia and New York City about the microaggressions they faced during their care. The women ranged in age from 16 to 46, with about 43 percent between 20 and 29.

Types of Microaggressions Reported

Microaggressions took various forms, including:

- Invalidation: Comments like “Calm down” or “You’re overreacting,” dismissing the woman’s feelings or concerns.

- Stereotyping: Accusations such as “You’re angry” when speaking assertively or confidently.

- Disrespect: Instances where women felt dismissed, ignored, or treated rudely by medical staff.

Nearly two in five women (38 percent) reported at least one instance of microaggression during their pregnancy care. Those who experienced one or more microaggressions had average systolic blood pressure readings 2.12 points higher and diastolic readings 1.43 points higher. Systolic blood pressure measures the pressure in arteries during a heartbeat, while diastolic measures the pressure between heartbeats.

Women living in areas with more structural racism had even greater differences in blood pressure: systolic readings were 7.55 points higher and diastolic readings were 6.03 points higher.

“For many people, this can make the difference between needing blood pressure-lowering medications or not,” said Dr. Natalie Cameron, an instructor in preventive medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

RELATED: Working While Black: Surviving Workplace Racism & Microaggressions

Tips for Facing Microaggressions

While structural and systemic changes are needed to address the root causes of racism and sexism in healthcare, you can adopt strategies to protect your well-being in the face of microaggressions:

- Document Experiences: Keep a record of incidents, noting dates, times, and details. This documentation can be valuable if the need arises to address concerns with healthcare providers or institutions.

- Seek Support: Share experiences with trusted friends, family, or support groups. Connecting with others who have faced similar challenges can offer emotional relief and practical advice.

- Advocate for Yourself: Use clear, assertive communication to express concerns and ensure that your needs are met. Phrases like, “I need you to listen to my concerns” can help redirect dismissive behavior.

- Choose Allies in Care: Whenever possible, work with healthcare providers or patient advocates who are culturally sensitive and understand the unique challenges faced by women of color.

- Prioritize Self-Care: Engage in activities that reduce stress and promote relaxation, such as mindfulness, yoga, or other forms of exercise.

Looking Ahead

Future research is needed to better explore how racism influences blood pressure, as well as its effects on the health of mothers and their infants. Researchers stress the long-term impact that racism and microaggressions can have on overall health.

“This work serves as a reminder of the long-term impact that racism can have on one’s overall health,” said senior researcher Dr. Lisa Levine, director of the Pregnancy and Heart Disease Program at the University of Pennsylvania. “The magnitude of these types of physiologic changes may become cumulative over time and lead to the inequities we see in many health outcomes.”

By highlighting the prevalence and impact of microaggressions, the study underscores the urgency of creating equitable healthcare environments where all women feel respected and supported.