The Elaine massacre began on September 30th 1919 and went through October 1, 1919 at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. An estimated 100 to 237 African Americans and five whites were killed, and more wounded. At least two and possibly more victims were killed by Federal troops. The exact number of blacks killed is unknown because of the wide rural area in which they were attacked. Many quote upwards of 800 Blacks were killed. According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, "the Elaine Massacre was by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas history and possibly the bloodiest racial conflict in the history of the United States".

Located in the Arkansas Delta, Phillips County had been historically developed for cotton plantations, and was worked by African-American slaves before the Civil War. In the early 20th century the population was still overwhelmingly black, as most freedmen and their descendants had stayed as illiterate farm workers and sharecroppers.

With sharecropping, the landowner sold the crop whenever and however he saw fit. At the time of settlement, landowners generally never gave an itemized statement to the black sharecroppers of accounts owed, nor details of the money received for cotton and seed. The farmers were disadvantaged as many were illiterate. It was an unwritten law of the cotton country that the sharecroppers could not quit and leave a plantation until their debts were paid.

They often amassed considerable debt at the plantation store before that time, as they had to buy supplies, including seed, to start the next season.

Black farmers began to organize in 1919 to try to negotiate better conditions, including fair accounting and timely payment of monies due them by white landowners. Robert L. Hill, a black farmer from Winchester, Arkansas, had founded the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. He worked with farmers throughout Phillips County. Its purpose was "to obtain better payments for their cotton crops from the white plantation owners who dominated the area during the Jim Crow era. Black sharecroppers were often exploited in their efforts to collect payment for their cotton crops."

African Americans outnumbered whites in the area around Elaine by a ten-to-one ratio, and by three-to-one in the county overall. White landowners controlled the economy, selling cotton on their own schedule, running high-priced plantation stores where farmers had to buy seed and supplies, and settling accounts with sharecroppers in lump sums, without listing items.

Born a slave in rural Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ida Wells-Barnett grew up during emancipation and Reconstruction. She had raised her five siblings on meager wages as a rural schoolteacher. She became one of the most passionate anti-lynching activists and the first African American woman to own her own newspaper.

She was there and reported on the activity in Elaine. Here's an excerpt from her reporting:

“I was at Hoop Spur Church that night to lodge meeting. I do know that four or five automobiles full of white men came about fifty yards from the church and put the lights out, then started shooting in the church with about 200 head of, men, women and children. I was on the outside of the church and saw this for myself. Then I ran after they started firing in on the church. I don’t know if anybody got killed at, all. I went home and stayed home that night, then the white people was sending word that they was going to kill all the black people, then I run back in the woods and hid two days then the soldiers came then, I made it to them. I was carried in Elaine and put in the school house and I was there eight days. Then I was brought to Helena and put in jail and whipped near to death and was put in an electric chair to make me lie on other Negroes. It was not the union that brought this trouble; it was our crops. They took everything I had, twenty-two acres of cotton, three acres of corn. All that was taken from me and my people. Also all my household goods. Clothes and all. All my hogs, chickens and everything my people had. I was whipped twice in jail. These white people know that they started this trouble. This union was only for a blind. We were threatened before this union was there to make us leave our crops.”

On September 29, representatives of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America met with about 100 black farmers at a church near Elaine to discuss how to obtain fairer settlements from landowners. Whites had resisted union organizing by the farmers and often spied on or disrupted such meetings. In a confrontation at the church, a county deputy was shot and killed, and another white man wounded.

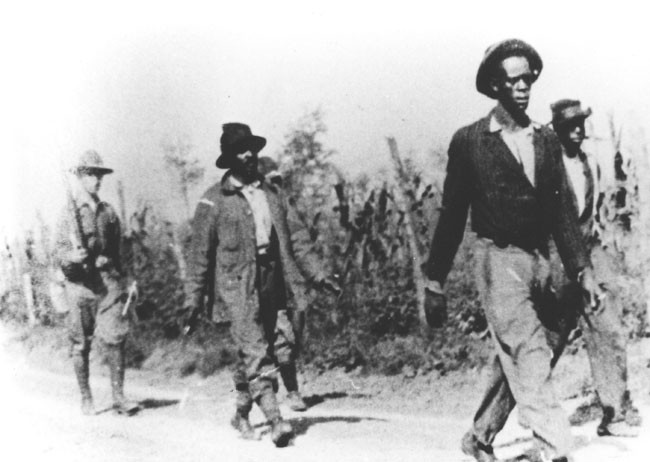

The county sheriff organized a posse, and whites gathered to put down what was rumored as a "black insurrection". Other whites entered Phillips County to join the action, making a mob of 500 to 1000. They attacked blacks on sight...

...across the county. The governor called in 500 federal troops, who arrested nearly 260 blacks and were accused of killing some. Over a three-day period, fatalities included 100-240 blacks, with some estimates of more than 800, as well as five white men. The events have been subject to debate, especially the total of black deaths.

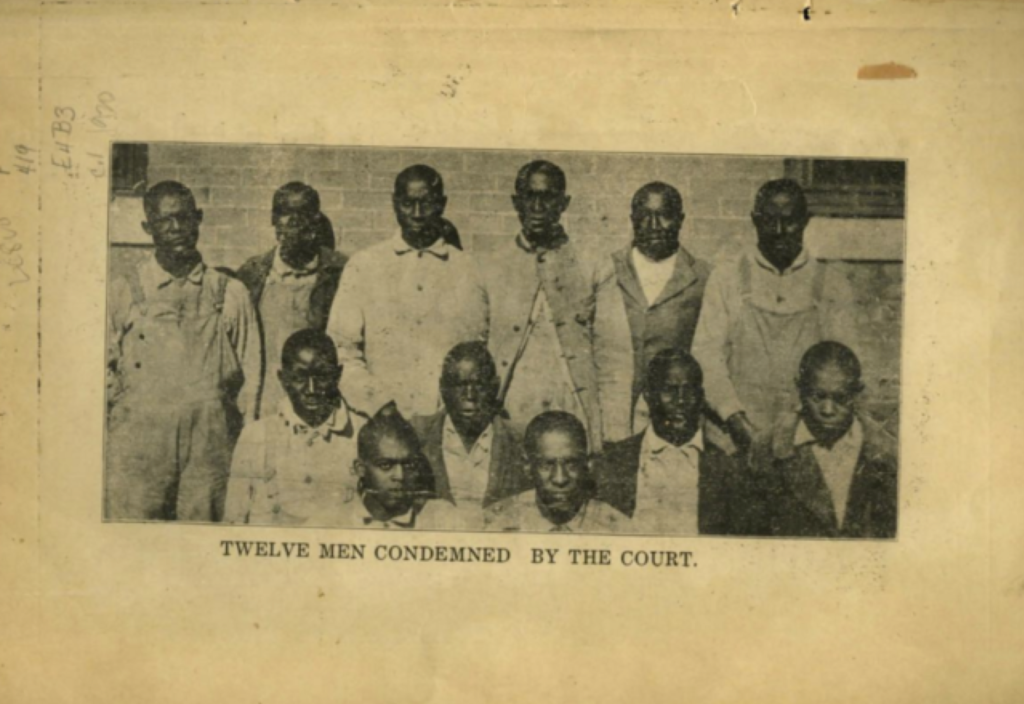

The only men prosecuted for these events were 122 African Americans, with 73 charged with murder. Twelve were quickly convicted and sentenced to death by all-white juries for murder of the white deputy at the church. Others were convicted of lesser charges and sentenced to prison. During appeals, the death penalty cases were separated. Six convictions (known as the Ware defendants) were overturned at the state level for technical trial details. These six defendants were retried in 1920 and convicted again, but on appeal the State Supreme Court overturned the verdicts, based on violations of the Due Process Clause and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, due to exclusion of blacks from the juries. The lower courts failed to retry the men within the two years required by Arkansas law, and the defense finally gained their release in 1923.

The six other death penalty cases (known as Moore et al.) ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court overturned the convictions in the Moore v. Dempsey (1923) ruling. Grounds were the failure of the trial court to provide due process under the Fourteenth Amendment, as the trials had been dominated by adverse publicity and the presence of armed white mobs threatening the jury. This was a critical precedent for the "Supreme Court's strengthening of the requirements the Due Process Clause imposes on the conduct of state criminal trials.