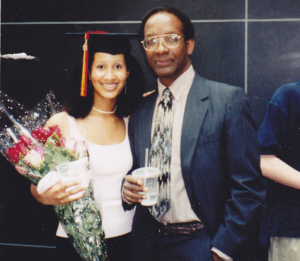

courtesy of Audrey Davis.

Eighteen years ago, when I was a senior at Carleton College in Minnesota, I received a phone call from my dad. He said three words that would forever change the trajectory of my life: “I have cancer.” I soon learned that his diagnosis of Stage IV colorectal cancer also held a grim prognosis for his particular case and that he did not expect to attend my graduation that spring due to the aggressive chemotherapy and radiation treatments that would be needed. Instead, my dad’s brother and best friend, my uncle Wilfrid, cheered me on as I walked the stage to collect my diploma that May.

Dad, Wilfrid, and their brother, Jacques, emigrated from Haiti to the U.S. as teenagers without their parents, who died on the island before any of them became adults. They trusted each other with their lives and livelihoods as they traveled from everything that they knew to a completely foreign country and language.

Wilfrid is now a retired internal medicine doctor and remains my biggest cheerleader. He and my parents supported me in my decision to pivot away from plans to move to Washington State after graduation and instead return home to the East Coast so that I could help with caregiving for my dad. Uncle Wilfrid remained in Illinois with his immediate family while I collaborated with our relatives in Philadelphia to coordinate my dad’s care and treatment.

When my dad and I went to his appointments together, I noticed a few things—I was disappointed and surprised to see that even in a bustling multicultural city and within a university hospital, the majority of individuals who resembled my Black Haitian father were primarily custodial engineers, support staff, and some allied health professionals. I was incensed by certain assumptions made about my dad’s ability to comprehend the information given to him—this was a man who spoke over five languages fluently! His thick Caribbean accent remained, but he was treated as though he could not comprehend information about his own body and care unless I, or in certain cases, Uncle Wilfrid, intervened.

His doctor briefly mentioned clinical trials as a treatment option, but the idea was not revisited until my dad asked additional questions. And when these questions were asked, he posed them to Uncle Wilfrd rather than his doctor. Dad knew my uncle would not make negative assumptions about his intellect or intelligence. He knew he would be honest with him about the potential risks and benefits of clinical trial participation. They had mutual respect for each other, and the care and compassion that my uncle had for my dad was believed and felt wholeheartedly.

Here is what we know: Black and African-American people make up approximately 14.4 percent of the population in the United States. A recent JAMA Network Open review concluded that from 2017-2022, only 4.4 percent of clinical trial participants for any cancer type were Black or African American. Unfortunately, Black people are more likely than their White compatriots to be diagnosed with female breast, lung, and colorectal cancers at late stages. Moreover, the overall five-year cancer survival rate for Black patients is lower than it is for White people, and of all races and ethnicities, Black people have the highest cancer death rates.

Why is this? Although the causes for these differences in clinical trial participation rates are multifaceted and multifactorial, one major reason is medical mistrust and distrust among Black Americans. Medical mistrust (which can result in medical distrust) can be conceptualized as a “protective response against the pervasive, interlocking structural inequalities that result in restricted access to resources, including housing, educational opportunities, employment, and healthcare, in addition to daily experiences of racism, stigma and discrimination.”

My dad was eventually willing to engage in clinical research because he trusted my uncle. He knew that Uncle Wilfrid was a competent medical doctor well-versed in academic research. He was certain that my uncle cared about him and had his best interests in mind. There are ways to improve clinical trial participation among Black and African American cancer patients at both the individual and systemic levels and my uncle’s interactions with my dad underscore that the onus is not solely on Black and African American patients.