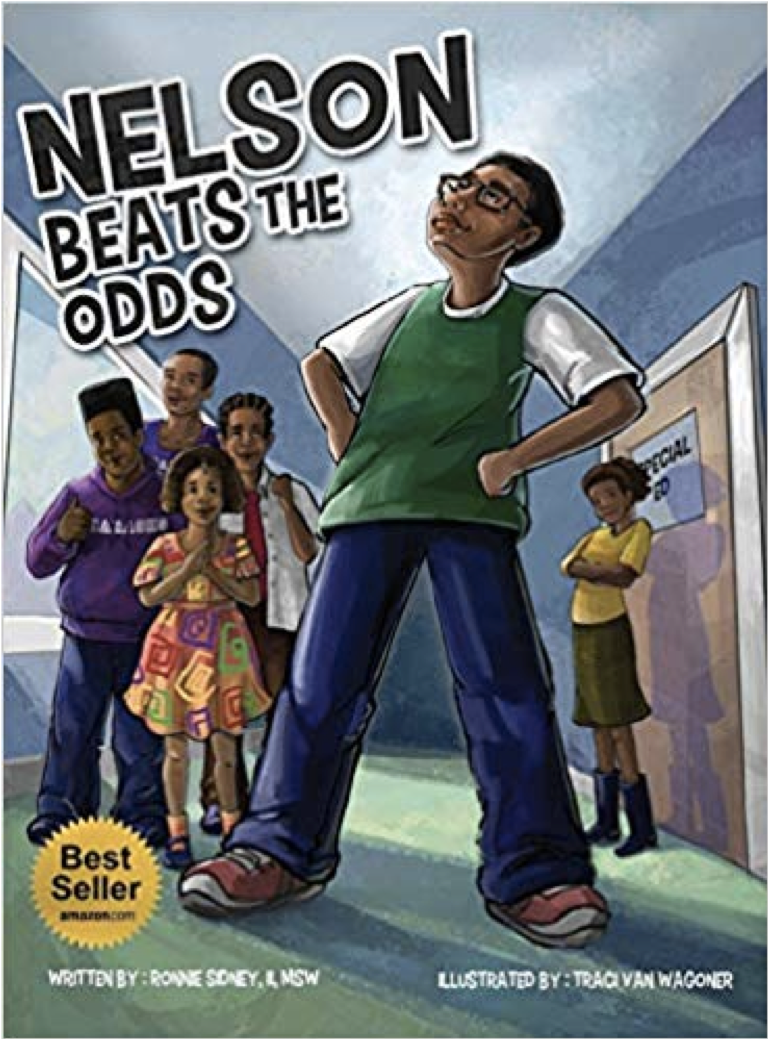

“Nelson Beats the Odds,” is a novel about a young man diagnosed with a learning disability and ADHD. With the help of his parents and special education teacher, Nelson graduates from college and becomes a social worker.

The book may be a great story and even might make a great movie, but the book is not just a story, it's the real-life tale of Ronnie Sidney.

Sidney explains that he wrote the book, “to inspire young people who’ve been diagnosed with learning disabilities and mental health disorders to overcome their challenges.”

Diagnosed with ADHD while in elementary school, Sidney, II, spent seven years in special education in the Essex County Public School system in Tappahannock, Virginia. Sidney hated the stigmatization of special education and began to lose interest in school altogether.

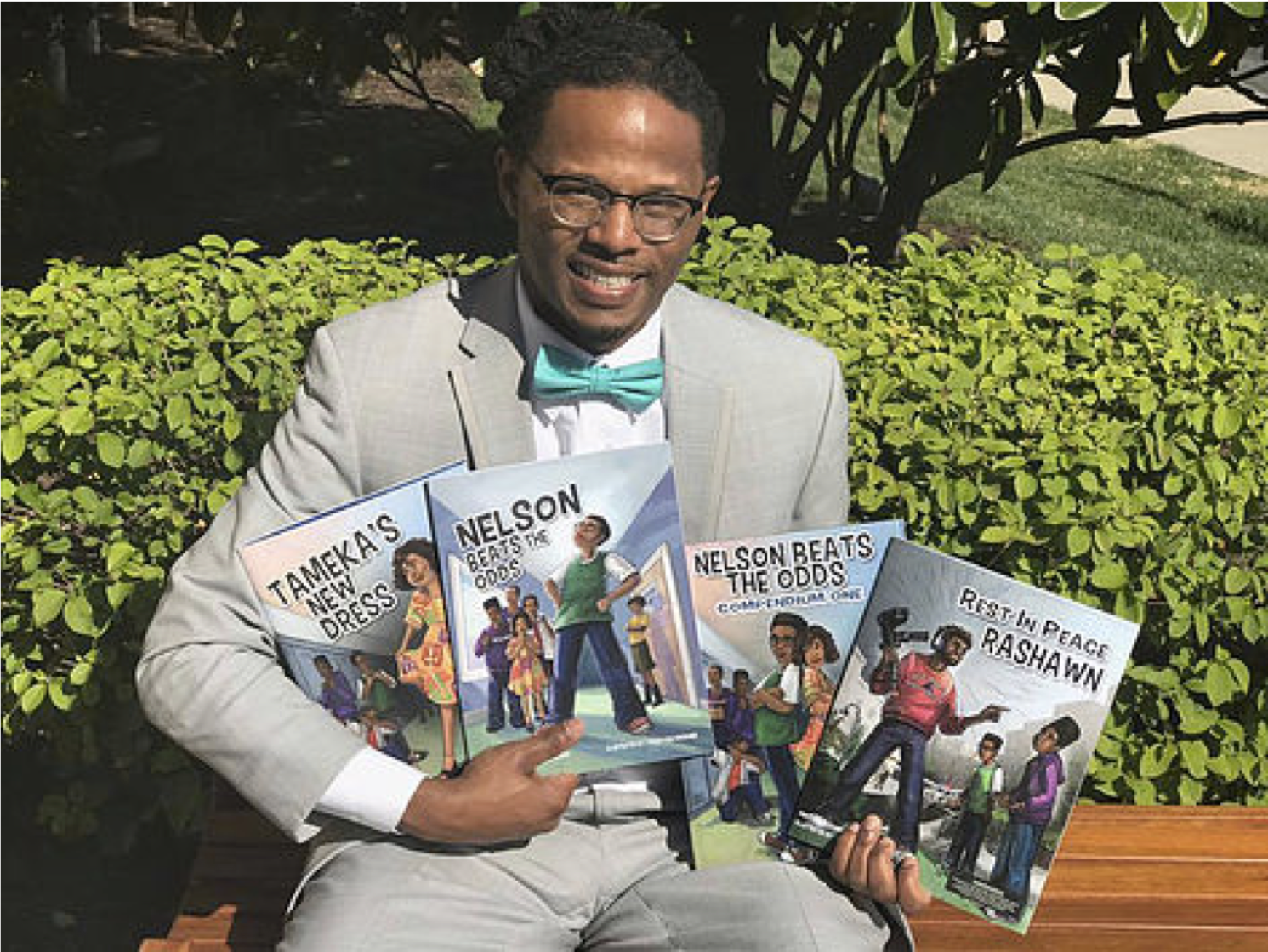

Despite all of that, he graduated from Essex High School in 2001, but with a 1.8 GPA. With limited options regarding four-year colleges, he enrolled in J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College in Richmond, Virginia, where he did so well that he was able to transfer to a four-year university the following year. Sidney received a bachelor’s degree in human services in 2006.

Ronnie suffered from Dysgraphia.

Dysgraphia is a learning disability that affects writing abilities. It can manifest itself as difficulties with spelling, poor handwriting and trouble putting thoughts on paper. Because writing requires a complex set of motor and information processing skills, saying a student has dysgraphia is not sufficient. A student with disorders in written expression will benefit from specific accommodations in the learning environment, as well as additional practice learning the skills required to be an accomplished writer.

Today, he has a Master of Social Work degree and has spent over eight years in the mental health and academic counseling fields, currently working as an outpatient therapist at the Middle Peninsula-Northern Neck Community Services Board.

Sidney says that he thought about telling his story for a long time, but was ashamed of his disabilities for most of his life. Once he earned his master’s degree, however, he thought, “Now no one could tell me I wasn’t smart.”

Sidney said earning that degree helped him to realize that he was finally in a position where he wanted to share his story. “It just felt like it was the time to give back,” he says, and in writing the story, Sidney confesses, sharing his past actually helped him deal with the shame he still carried within him.

“I always kind of had it in me to prove people wrong,” Sidney says. “I always felt like the underdog; I felt like people thought I wasn’t as good as them, yet deep inside I knew I was. I always felt like I had the potential to do great things.”

Sidney shares that when he was in middle school and performing at his worst, he suffered from poor self-esteem, both academically and socially. Then his special education teacher entered the picture. “She was really the first teacher that made me feel smart,” he says. “She knew that there were things I could improve on — organization, handwriting, my...

...hyperactivity, but she could also see what was inside.”

Sidney also credits his parents for always supporting him, and advises other parents to believe in their kids: “Just love them and support them,” Sidney urges.

“Advocate for them,” he encourages. “It is so easy for children with disabilities to feel like no one believes in them, but it just takes that one person who will never give up on you, that can help you turn your life around.”

Sidney says that he kept busy in college. He used hyperactivity to his advantage – getting involved in a variety of activities. He also says that while he started out majoring in business, he switched to human services, wanting to do something with more heart.

“Money wasn’t the motivating force for me,” he says. “I wanted to do something that I was passionate about.”

“I always enjoyed working with disadvantaged youth – those that had everything going against them, those kids that everyone else had given up on. I could see the value in them, like my special education teacher could see in me.”

“Don’t even look at it as a disability,” Sidney advises. “ADHD for me has been a source of strength in some ways that has actually helped me get my book written and out into the marketplace.”

Sidney also founded a healing workshop called “Creative Medicine: Healing Through Words,” a therapeutic writing program he developed with a mentor of his. The program uses expressive writing, bibliotherapy, positive psychology, dialogue and self-reflection to help those incarcerated learn how to share their stories.

He also does a similar program out into the community and schools and uses pieces of it in the therapeutic workshops he leads. Sidney emphasizes the importance of addressing our vulnerabilities and shame.

“You can learn how to use your challenges as a strength,” he says. “There is just no other way.”