She also holds patents in Japan, Canada and Europe.) With her Laserphaco Probe, Bath was able to help restore the sight of individuals who had been blind for more than 30 years.

In 1993, Bath retired from her position at the UCLA Medical Center and became an honorary member of its medical staff. That same year, she was named a “Howard University Pioneer in Academic Medicine.”

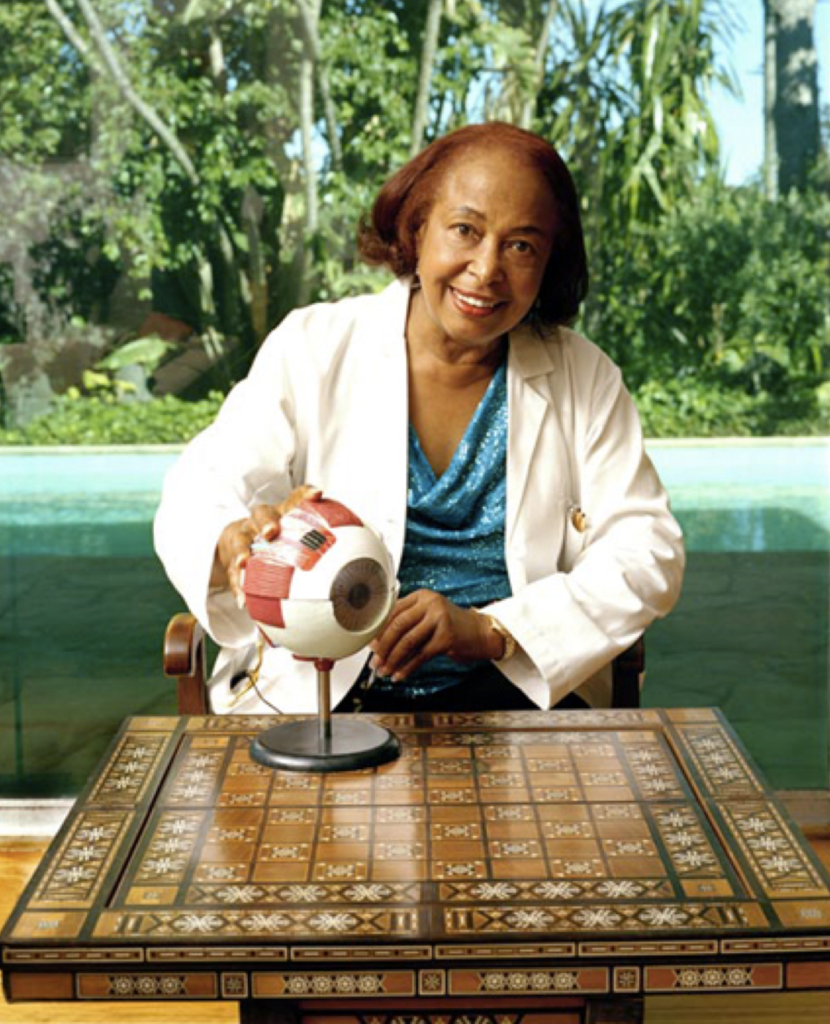

Dr. Bath’s greatest passion was always fighting blindness. Before her death in 2019, her “personal best moment” occurred on a humanitarian mission to North Africa, when she restored the sight of a woman who had been blind for thirty years by implanting a keratoprosthesis. “The ability to restore sight is the ultimate reward,” she says.

To be honest, I’ve never heard of Dr. Bath before this year. I was blind, but now I see!