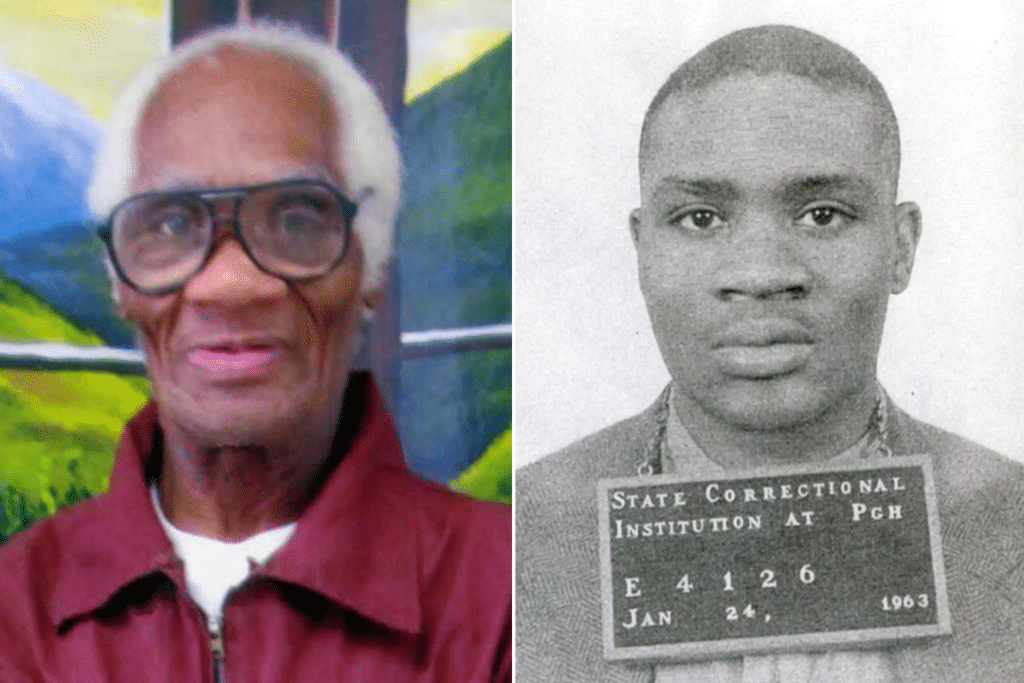

The nation's longest-serving juvenile inmate who spent 68 years behind bars is settling into a whole new world after he finally walked free last week.

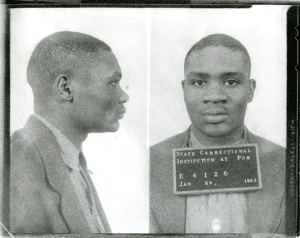

Joe Ligon was incarcerated in February 1953 at the age of 15, given a mandatory life sentence after pleading guilty to charges stemming from a robbery and stabbing spree in Philadelphia with four other teenage boys. The crime left six people wounded and two people -- identified by the Philadelphia Inquirer as Charles Pitts and Jackson Hamm -- dead.

Nearly 7 decades behind bars, just about everything Ligon had known is gone or different. He's been in prison behind some of the world's most historical events and family trials and triumphs have come and gone.

"I got caught up, in terms of being in the streets," Ligon told CNN after his release last week.

While a so-called degree of guilt hearing found Ligon guilty of two counts of first-degree murder, and Ligon admitted to stabbing at least one of the eight people stabbed that day, his attorney Bradley Bridge told CNN that his client maintains he never killed anyone.

He turned down another offer of parole in 2017, after a ruling by the US Supreme Court made him eligible.

A year before, in 2016, the court had decided that Miller v. Alabama, a 2012 case in which mandatory juvenile life sentences without the prospect of parole were deemed unlawful, should be applied retroactively. The decision effectively resentenced Ligon to 35 years to life, and made him eligible for parole since he had been in prison for over 60 years.

But Ligon rejected the offer again, stating parole would not grant him the freedom he desired after decades in prison.

"The state parole board presumably would have released him but on condition that he would be under their supervision for the rest of his life," Bridge said. "He chose not to seek parole under those terms."

According to Daily Mail, while most people from Ligon's life before prison are no longer around, he isn't alone. Philadelphia's Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project (YSRP) has been working tirelessly to make his transition into post-prison life as smooth as possible.

"As much as the world has changed since Mr Ligon first went to prison, he has also changed. His experience in coming back is basically as a new man," Eleanor Myers, a senior adviser at YSRP, to Daily Mail.

'He is incredibly cheerful and amazed at the changes in Philadelphia since 1953, in particular the tall buildings.

'He has talked about those in his family who are gone and cannot be together for his homecoming. He seems to miss them especially.

"There is a large community of juvenile lifers who knew Joe for many years in prison. They will undoubtedly become his new circle of friends and supporters."

How He Will Re-enter Society

With so much that has changed since he went into prison, how will Ligon adapt?

The first thought that comes to mind is the scene from the movie 'Shawshank Redemption' with Morgan Freeman. The story followed the life of prisoners who were locked up for decades. When Morgan Freeman's character was finally released from prison, he didn't know how to act, what to do or what he was allowed or not allowed to do with his newborn freedom. He had been locked up for so long, prison had truly become his life.

The Returning Home study at the Urban Institute has shined the light on many health-related challenges associated with reentry, including a special focus on returning prisoners with serious mental and physical illness in Cincinnati, Ohio, as well as a study on the health care Chicago prisoners receive during prison and the health challenges they face after release. In addition, researchers at the Urban Institute explored evidenced-based housing programs that serve persons with mental illness who have had contact with the criminal justice system and identified various programs serving this population across the country.

Recent Findings from the Urban Institute on Health and Reentry

- A substantial number of prisoners have been diagnosed with a physical or mental health condition. Returning Home findings show that between nearly 30 and 40 percent of respondents reported having a chronic physical or mental health condition, with the most commonly reported conditions including depression, asthma, and high blood pressure. In New Jersey, about a third of prisoners released in 2002 had been diagnosed with at least one chronic and/or communicable physical or mental health condition.

- More prisoners report being diagnosed with a medical condition than report receiving medication or treatment for the condition while incarcerated. While 30 percent of Illinois Returning Home respondents reported having a physical or mental health condition, only 12 percent reported having taken medication on a regular basis while in prison. In a small study of prisoners in Ohio, over half reported being diagnosed with depression, but only 38 percent of the sample reported receiving treatment or taking prescription medication for depression. Similarly, 27 percent reported having asthma, yet less than 14 percent reported receiving treatment for asthma.

- Many corrections agencies lack discharge planning and preparation for addressing health care needs upon release, making continuity of care difficult. Less than 10 percent of prisoners in the Illinois Returning Home study reported receiving referrals to health care or mental health care services in the community. In fact, respondents who reported having fair or poor health were no more or less likely to receive referrals to health care in the community than those reporting to be in good general health. 10 In addition, only 20 percent of respondents in the small study of Ohio prisoners reported programming or assistance to prepare them to address their health care needs upon release.

Ligon grew up in a different world: a farm in Alabama, where he abandoned school in the third or fourth grade — he said he couldn’t stand being in big groups — much as he would reject educational offerings in prison.

“I’m just a stubborn type of person,” Ligon said. “I was born that way.”

His parents enrolled him in school in Philadelphia when he was 13, but he couldn’t keep up. He was still illiterate when he was arrested at age 15. He believes he was scapegoated as the new kid, the outsider.

A loner, he grew to pride himself on his janitorial skills. In Graterford prison, he learned to read and write. He trained as a boxer there, developing a military-style workout regimen he continues to this day, despite his arthritis.

He never applied for commutation, though he could have had a strong chance at clemency in the 1970s, when hundreds of Pennsylvania lifers were released. Instead, he put his faith in Bridge and waited for the day he’d be released. To prepare himself for modern society, he watched world news on a small TV in his cell.

When asked about how he thinks he'll survive when gets back out in this brand new world, Ligon had one simple answer.

“I like my chances,” he said. “I really like my chances in terms of surviving.”