In less than four hours, Robert Smalls had done something unimaginable: In the middle of the Civil War, this black male slave had taken over a heavily armed Confederate ship and delivered it, himself, along with 16 other black passengers (eight men, five women and three children) from slavery to freedom.

In less than four hours, Robert Smalls had done something unimaginable: In the middle of the Civil War, this black male slave had taken over a heavily armed Confederate ship and delivered it, himself, along with 16 other black passengers (eight men, five women and three children) from slavery to freedom.

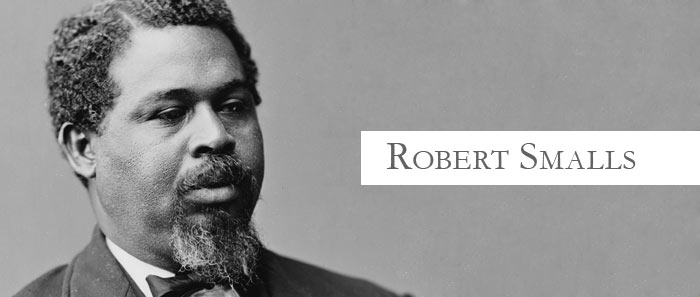

Robert Smalls was a 22-year-old mulatto slave born on April 5, 1839, behind his owner’s city house at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, S.C. His mother, Lydia, served in the house but grew up in the fields, where, at the age of nine, she was taken from her own family on the Sea Islands. It is not clear who Smalls’ father was.

The McKee family, who owned Robert and her mother, seem to favor Robert Smalls over the other slave children, so much so that his mother worried he would reach manhood without fully understanding how horrid slavery really was. To educate him, she arranged for him to be sent into the fields to work and watch slaves at “the whipping post.”

The result of this lesson led Robert to be defiant and he frequently found himself in the Beaufort jail.

Smalls mother then asked the slave master to allow him to go to Charleston to be "rented out to work.” And again her wish was granted. By the time Smalls turned 19, he had tried his hand at a number of city jobs and was allowed to keep one dollar of his wages a week (his owner took the rest).

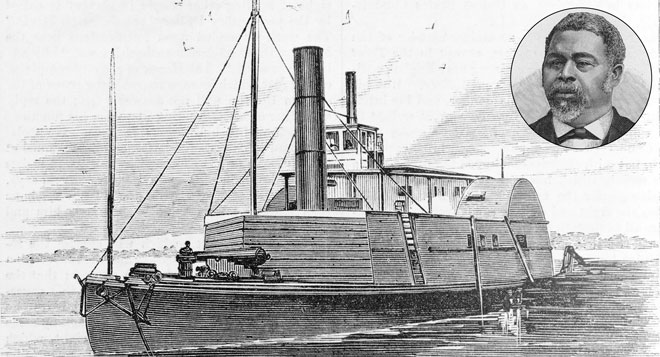

That was where he earned his job on a ship called, the Planter. It’s also where he met his wife, Hannah, a slave of the Kingman family working at a Charleston hotel. With their owners’ permission, the two moved into an apartment together and had two children: Elizabeth and Robert Jr. Being in love and longing for a permanent union, Smalls asked his wife’s owner if he could purchase his family outright; they agreed but at a steep price: $800.

While Smalls couldn’t afford to buy his family on shore, he knew he could win their freedom by sea — and so he told his wife to be ready for whenever opportunity presented itself.

That opportunity didn't take long to come and on the night of May 12, Smalls took advantage. Once the white officers are on shore, Smalls confides his plan to the other slaves on board.

At 2:00 a.m. on May 13, Smalls put on Capt. Rylea’s straw hat and orders the Planter’s skeleton crew to hoist the South Carolina and Confederate flags as decoys. Easing out of the dock, in view of Gen. Ripley’s headquarters, they pause at the West Atlantic Wharf to pick up Smalls’ wife and children, along with four other women, three men and another child.

According to NPR, at 3:25 a.m., the Planter accelerates. From the pilot house, Smalls blows the ship’s whistle while passing Confederate Forts Johnson and Fort Sumter. Smalls not only knows all the right Navy signals to flash; he even folds his arms like Capt. Rylea, so that in the shadows of dawn, he passes convincingly for white.

Upon approaching a Union blockade, Smalls orders his crew to replace the Palmetto and Rebel flags with a white bed sheet his wife brought on board. Not seeing it, Acting Volunteer Lt. J. Frederick Nickels of the U.S.S. Onward orders his sailors to “open her ports.”

In The Negro’s Civil War, the dean of Civil War studies James McPherson quotes the following eyewitness account: “Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’ ” That man is Robert Smalls, and he and his family and the entire slave crew of the Planter are now free.

Officer Samuel Francis Du Pont, at Port Royal, Hilton Heads Island, described Smalls as “very intelligent contraband.” Du Pont writes a letter to the Navy secretary in Washington, stating, “Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feet so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter gun], presuming it would be a matter of interest.” He “is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been.”

Smalls may not have had the $700 he needed to purchase his family’s freedom before the war; now, because of his bravery and his inability to purchase his wife, the U.S. Congress on May 30, 1862, passed a private bill authorizing the Navy to appraise the Planter and award Smalls and his crew half the proceeds for “rescuing her from the enemies of the Government.” Smalls received $1,500 personally, enough to purchase his former owner’s house in Beaufort off the tax rolls following the war, though according to the later Naval Affairs Committee report, his pay should have been substantially higher.

The Confederates didn't like anything they heard about Smalls and issued a $4,000 bounty on his head. But that didn't stop him.

In the North, Smalls was seen as a hero and personally lobbied the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to begin enlisting black soldiers. After President Lincoln acted a few months later, Smalls was said to have recruited 5,000 soldiers by himself. In October 1862, he returned to the Planter as pilot as part of Admiral Du Pont’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. According to the 1883 Naval Affairs Committee report, Smalls was engaged in approximately 17 military actions, including the April 7, 1863, assault on Fort Sumter and the attack at Folly Island Creek, S.C. For all his efforts, Smalls was promoted to the rank of captain himself, and from December 1863 on, earned $150 a month, making him one of the highest paid black soldiers of the war.

Following the war, Smalls continued to push the boundaries of freedom as a first-generation black politician, serving in the South Carolina state assembly and senate, and for five nonconsecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1874-1886) before watching his state roll back Reconstruction in a revised 1895 constitution that stripped blacks of their voting rights. He died in Beaufort on February 22, 1915, in the same house behind which he had been born a slave and is buried behind a bust at the Tabernacle Baptist Church. In the face of the rise of Jim Crow, Smalls stood firm as an unyielding advocate for the political rights of African Americans: “My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”