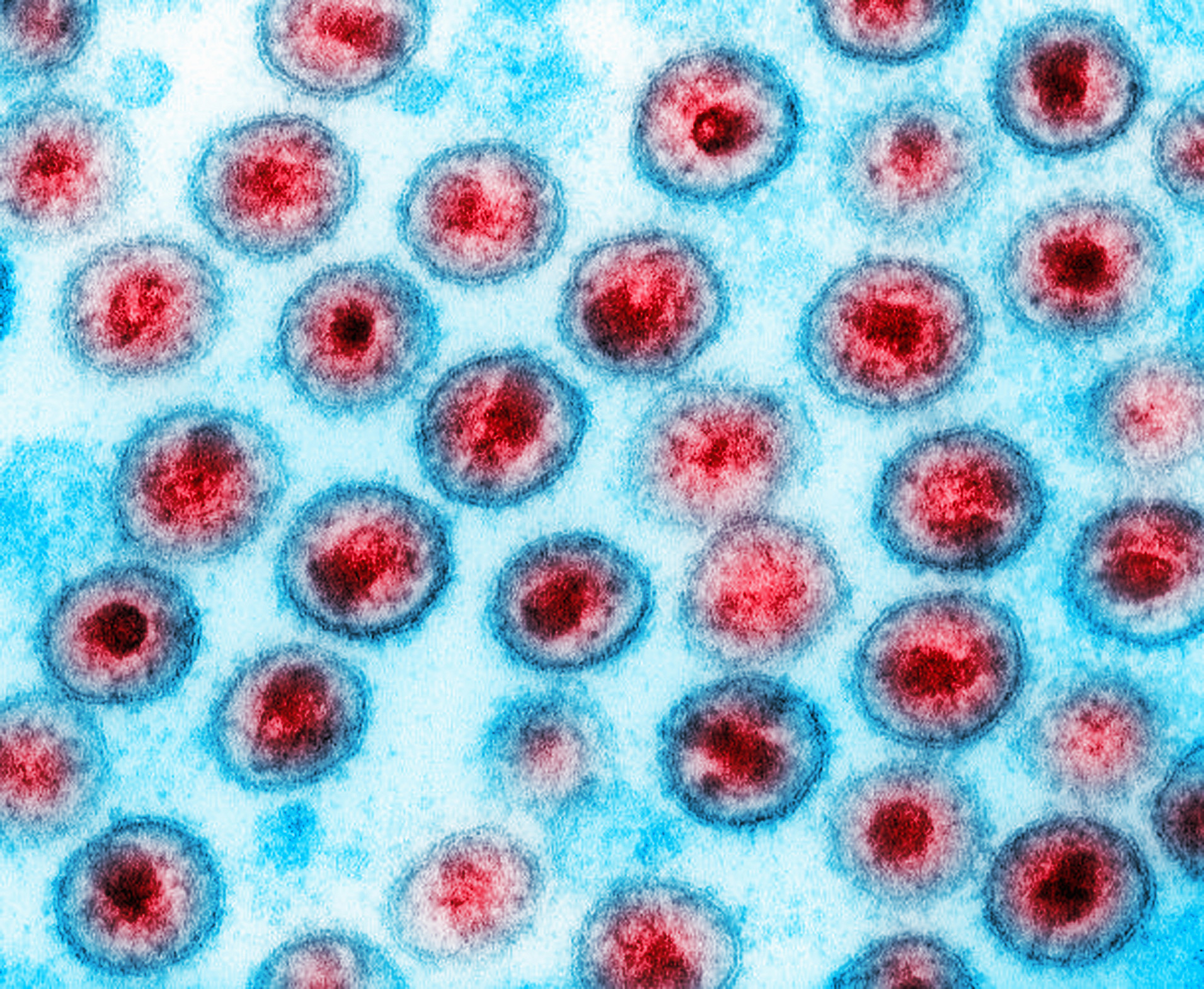

As if HIV and AIDS wasn't scary enough... The disease has stricken the Black community for decades and was starting to see some action against the disease, but for the first time in nearly 20 years, a team of scientists has detected a new strain of HIV.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that mutations in a virus can significantly change a pathogen’s infectiousness and severity of disease.

Now, new research from the University of Oxford finds a new variant of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, that is potentially more infectious and could more seriously affect the immune system.

So far, 109 people, most of whom live in the Netherlands, have the variant.

New HIV variant causes illness twice as fast

The new strain, called the VB variant, damages the immune system, weakening people’s ability to fight everyday infections and diseases much faster than the previous HIV strains, scientists say.

It also means that people who contract the new variant may develop AIDS faster.

Researchers also found that VB has a viral load (the amount of virus detected in blood) 3.5 to 5.5 times higher than the current strain, indicating that it could also be more infectious.

Other HIV Strains

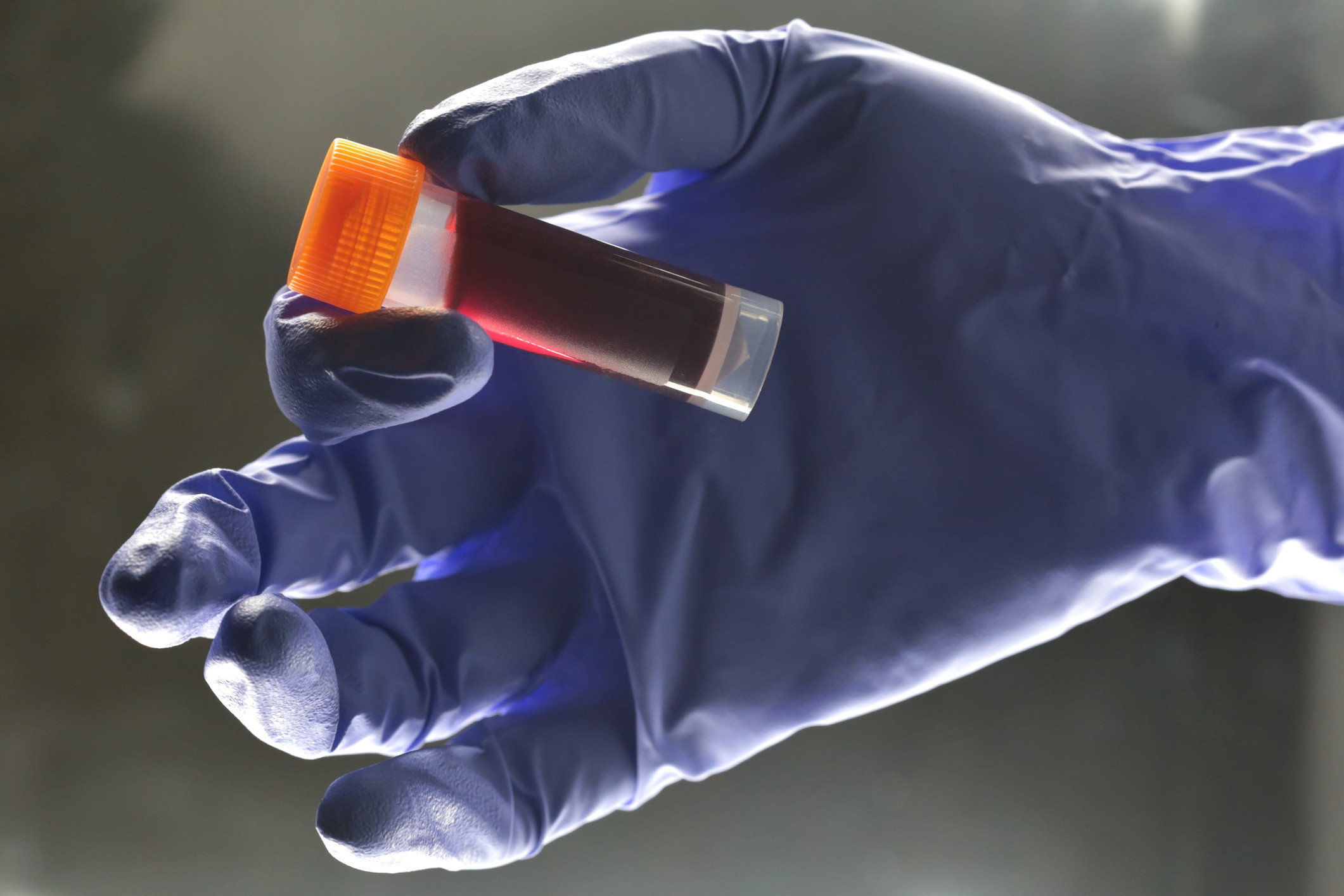

The last strain that was found, called HIV-1 group M subtype L, is extremely rare and can be detected by Abbott Lab’s current screening system. The company’s tests screen more than 60 percent of the global blood supply, she adds, noting it must detect every strain and “has to be right every time.”

In the early days of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s, some blood donors unaware that they had HIV added the virus to the blood supply. A large number of patients who needed regular blood transfusions—among them, many with hemophilia—ended up contracting HIV and often dying. The supply has been essentially clear of HIV for years, and Rodgers says efforts such as Abbott’s will help keep it that way.

"It can be a real challenge for diagnostic tests," Mary Rodgers, a co-author of the report and a principal scientist at Abbott, said. Her company tests more than 60% of the world's blood supply, she said, and they have to look for new strains and track those in circulation so "we can accurately detect it, no matter where it happens to be in the world."

More than 37 million people live with HIV worldwide—the most ever recorded. “People think it’s not a problem anymore, and we’ve got it under control. But, really, we don’t,” Sacha says.

Antiretroviral drugs inhibit the virus’s reproduction and spread, but they have significant side effects, he says. Even when drugs keep HIV under control, patients are at higher risk for blood cancer, cardiovascular complications, and other problems.

The danger from the virus persists. A radically new viral strain could evade detection in the blood supply, avoid being controlled by drugs and render future vaccines ineffective, Sacha says. “Viruses break through all the time, and we’re not ready to deal with them,” he adds, “just like what happened with the original HIV.”

For scientists to be able to declare that this was a new subtype, three cases of it must be detected independently. The first two were found in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1983 and 1990.

The two strains were "very unusual and didn't match other strains," Rodgers said. The third sample found in Congo was collected in 2001 as a part of an HIV viral diversity study (Notice, that all these strains were found in Africa).

The sample was small, and while it seemed similar to the two older samples, scientists wanted to test the whole genome to be sure. At the time, there wasn't technology to determine if this was the new subtype.

New Strain Of HIV Discovered. Should We Be concerned?

Many viruses and bacteria that cause disease have different strains or genetic varieties. Right now, we are in flu season. We get flu vaccinations each year because the main strain responsible for the flu changes every year and we must develop a new vaccine. The Human papillomavirus which causes genital warts, cervical and anal cancers, and head and neck cancers has over 100 strains referred to as genotypes. Most of these strains are harmless to people, but other specific genotypes are able to cause the diseases I listed.

The Hepatitis C virus (HCV) has six major strains, also referred to as genotypes. One of the most striking differences between these genotypes is their response to treatment.

For example, when we used a drug called interferon to treat hepatitis C, patients with genotype 4 could expect to get cured by treatment whereas patients with genotype 1a or 1b were far less likely to experience such a benefit. Fortunately, we now have easy to take medicines that can cure all genotypes of HCV in most cases with just a couple months of treatment (more on this topic in the future).

So what about HIV? There is a lot of variation in HIV strains. First of all, you should understand that there are two major types of HIV: HIV-1 and HIV-2. For the most part, whenever you hear HIV, it is referring to HIV-1. It is by far the major virus that infects people all over the world. HIV-2 is only found in parts of West Africa.

HIV-2 is a deadly virus just as HIV-1 but it causes disease slower than HIV-1. It is also spread sexually, through birth and coming into contact with infected blood. It is possible for a person to be infected by both HIV-1 and HIV-2 but fortunately that isn’t very common. The biggest concern with HIV-2 is that there are some classes of HIV medicines that do not work against the virus. None of the drugs in the Non-nucleoside class (efavirenz, rilpivirine, etravirine, doravirne) can suppress HIV-2. Also, some protease inhibitors don’t work (e.g. atazanavir) while others do (e.g. darunavir).

For HIV-1, the largest category of viruses are in group M and the different strains are referred to as subtypes. Subtypes are based on their genetic similarity and diversity. They are found in different geographical areas. What is amazing to observe is that most developed countries have the same HIV subtype. Throughout North America and Europe but also Latin America and the Caribbean, the predominant strain is HIV-1 subtype B.

This is quite significant because the most research has been done in subtype B virus. Diagnostic tests were developed to detect subtype B and all the drugs we used were developed for their effectiveness against subtype B virus. However, other subtypes predominate in developing countries. The most widespread strain of HIV is subtype C. It is found throughout Southern Africa, parts of East Africa, India and other parts of Asia. Approximately half of all HIV infections in the world are from subtype C virus. As I just mentioned, diagnostic tests early on were developed to detect subtype B virus and oftentimes were not able to recognize infections from other subtypes because of minor differences in their genetic makeup.

This created a problem where HIV infections were sometimes missed here in the US if the person had been infected with a different subtype and may have come from another country. I would say that in the last couple of decades, the tests have been improved such that this is no longer a problem. There are differences between different subtypes in how easily they are transmitted sexually and through birth and also how aggressively they cause disease. For example, in the country of Uganda, most people have either subtype A or subtype D virus. But these two are NOT the same! Subtype A viruses have a significantly higher rate of heterosexual transmission than subtype D viruses.

However, in the absence of treatment, subtype D virus causes more damage to the immune system and progresses nearly twice as fast to AIDS as subtype A. The good news is that unlike the case for HIV-2, for HIV-1, all HIV medicines work in all subtypes for the most part.

Now back to the story at hand. The new subtype identified has been designated subtype L. It has been isolated from the Congo in central Africa. From what we can tell so far, all medicines should be effective against this strain. We don’t think this strain is very widespread but we just don’t know yet because its discovery is so recent. There were specimens that had this virus that were from almost 20 years ago, but a new method of molecular genetic testing (called next-generation gene sequencing) allowed scientists to recognize the unique features of this virus and classify it as a new subtype.

HIV originated in Africa and spread to other parts of the world. Some scientists believe that HIV came into the human species from chimpanzees, yet HIV is very seldom found in wild chimpanzees. HIV-2 is found in a type of monkey called the Sooty mangabey, but it doesn’t cause disease in these monkeys. HIV doesn’t cause disease in most apes and monkeys because their bodies produce compounds which block infection by HIV.

These compounds are specialized proteins called restriction factors, and they can work in a variety of ways along with the immune system to fight HIV naturally. Humans also produce a variety of restriction factors which can seriously slow down the virus in our bodies and helps explain why HIV takes several years to progress to AIDS and cause death. Perhaps, by studying subtype L virus and people who are infected with that strain, we may discover new ways that our bodies can fight the virus through restriction factors or the immune system and possibly develop new treatments.

I’m sure we’ll be hearing more about subtype L HIV in the near future.

Dr. Crawford has over 25 years of experience in the treatment of HIV. While at Howard University School of Medicine, he worked in two HIV-specialty clinics at Howard University Hospital. He then did clinical research as a visiting scientist with the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. He served as the Assistant Chief of Public Health Research with the Military HIV Research Program where he managed research studies under the President’s Emergency Plan for AID Relief (PEPFAR) in four African countries.

Dr. Crawford has over 25 years of experience in the treatment of HIV. While at Howard University School of Medicine, he worked in two HIV-specialty clinics at Howard University Hospital. He then did clinical research as a visiting scientist with the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. He served as the Assistant Chief of Public Health Research with the Military HIV Research Program where he managed research studies under the President’s Emergency Plan for AID Relief (PEPFAR) in four African countries.

He is currently working in the Division of AIDS in the National Institutes of Health. He has published research in the leading infectious diseases journals and serves on the Editorial Board of the journal AIDS. Any views and perspectives in his articles on blackdoctor.org are not representative of any agency or organization but a reflection of his personal views.