Teonna Woolford has always wanted six kids. Why six?

“I don’t know where that number came from. I just felt like four wasn’t enough,” says Woolford, a Baltimore resident. “Six is a good number.”

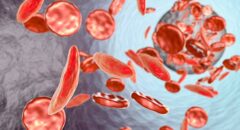

Woolford, 31, was born with sickle cell disease. The genetic disorder causes blood cells to become misshapen, which makes it harder for blood to carry oxygen and flow throughout the body. This can lead to strokes, organ damage, and frequent bouts of excruciating pain.

Sickle cell disease affects an estimated 100,000 people in the U.S., and the vast majority of them are Black. Federal and charitable dollars dedicated to fighting sickle cell disease pale in comparison to what is spent to combat other, less common diseases that mostly affect white patients.

Physicians and researchers say the disease is a stark example of the health inequities that pervade the U.S. health system. A poignant expression of this, according to patient advocates, is the silence around the impact that sickle cell disease has on fertility and the lack of reproductive and sexual health care for the young people living with the complex disease.

Woolford’s sickle cell complications have run the gamut. By the time she was 15, her hip joints had become so damaged that she had to have both hips replaced. She depended on frequent blood transfusions to reduce pain episodes and vascular damage, and her liver was failing.

“So many complications, infections, hospitalizations, and so by the time I graduated high school, I just felt defeated [and] depressed,” Woolford shares, speaking from a hospital bed in Baltimore. She had experienced a sickle cell pain crisis a few days earlier and was receiving pain medication and intravenous fluids.

RELATED: Sickle Cell Warrior Writes The Children’s Book She Never Had Growing Up

Learning she may be infertile

In her late teens, Woolford sought out a bone marrow transplant, a treatment that enables the sickle-shaped cells in the patient’s body to be replaced with healthy cells from a stem cell donor. The procedure comes with risks, and not everyone is eligible. It also relies on finding a compatible donor. But if it works, it can free a person from sickle cell disease forever.

Woolford couldn’t find a perfect match, so she enrolled in a clinical trial in which doctors could use a “half-matched” donor. As part of the bone marrow transplant, patients first receive chemotherapy, which can impair or eliminate fertility. Woolford hesitated. After all, her ideal family included six children.

When she told her doctor about her worry, his response crushed her: “This doctor, he looked at me, and he was like, ‘Well, I’ll be honest, with all the complications you’ve already had from sickle cell, I don’t know why you’re even