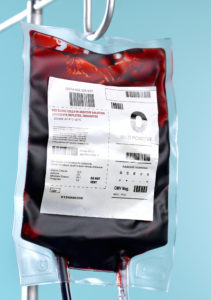

As the coronavirus pandemic rolls on, pharmaceutical companies everywhere are scrambling to try to get a vaccine or treatment out in order to go back to some type of normalcy.

As the coronavirus pandemic rolls on, pharmaceutical companies everywhere are scrambling to try to get a vaccine or treatment out in order to go back to some type of normalcy.

This week, researchers may have found a break that could help bring about that faster.

Two studies published this week in Blood Advances publication suggest people with a certain blood type may have a lower risk of COVID-19 infection and reduced likelihood of severe outcomes, including organ complications, if they do get sick.

These new studies add to evidence that there may be an association between blood type and how your body reacts or fights against COVID-19.

Blood type O may offer some protection against COVID-19 infection, according to the previous study.

"Blood group O is significantly associated with reduced susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection," the study authors wrote, meaning that people with type O blood seemed to be less likely to become infected. SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes Covid-19.

The findings of the study are limited because blood type information was available for just 62 percent of those who were tested.

Before you get happy and start checking everyone in your family's blood type, it is also important to note that people with type O blood can and do become infected.

Researchers compared Danish health registry data from more than 473,000 individuals tested for COVID-19 to data from a control group of more than 2.2 million people from the general population.

Among the COVID-19 positive, they found fewer people with blood type O and more people with A, B, and AB types.

"The study suggests if you have type O, you have a slightly lower risk," Dr. Roy Silverstein, chair of medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, said. "But it's a small decrease," he said, adding that blood type does not equate to zero percent risk.

Silverstein, who is also a former president of the American Society of Hematology, was not involved with the new studies.

In general, the rarest blood type is AB-negative and the most common is O-positive. Here's a breakdown of the rarest and most common blood types by ethnicity, according to the American Red Cross.

O-positive:

African-American: 47 percent

Asian: 39 percent

Caucasian: 37 percent

Latino-American: 53 percent

O-negative:

African-American: 4 percent

Asian: 1 percent

Caucasian: 8 percent

Latino-American: 4 percent

A-positive:

African-American: 24 percent

Asian: 27 percent

Caucasian: 33 percent

Latino-American: 29 percent

A-negative:

African-American: 2 percent

Asian: 0.5 percent

Caucasian: 7 percent

Latino-American: 2 percent

B-positive:

African-American: 18 percent

Asian: 25 percent

Caucasian: 9 percent

Latino-American: 9 percent

B-negative:

African-American: 1 percent

Asian: 0.4 percent

Caucasian: 2 percent

Latino-American: 1 percent

AB-positive:

African-American: 4 percent

Asian: 7 percent

Caucasian: 3 percent

Latino-American: 2 percent

AB-negative:

African-American: 0.3 percent

Asian: 0.1 percent

Caucasian: 1 percent

Latino-American: 0.2 percent

Can a person's Blood Type Change Over Time?

A person's blood type is based on whether or not they have certain molecules or proteins — called antigens — on the surface of their red blood cells, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Two of the main antigens used for blood typing are known as "A antigen" and "B antigen." People with type A blood only have A antigens on their red blood cells and those with type B blood have only B antigens. Individuals with type AB blood have both; people with type O blood have neither.

Another protein, the "Rh factor" – also known as the "Rhesus" system – is also present or absent on red blood cells.

A person's blood type is designated as "positive" if they have the Rh protein on their red blood cells, and "negative" if they don't have this protein.

Even still, a second smaller study also published this week seems to boost those findings. Researchers in Canada looked at data on 95 Covid-19 patients in Vancouver from February to April.

All were sick enough to be hospitalized in intensive care units.

Again, researchers found differences in blood types. This time, certain types appeared to be associated with worse outcomes.

"A higher proportion of Covid-19 patients with blood group A or AB required mechanical ventilation and had a longer ICU stay compared with patients with blood group O or B," the study authors wrote.

Types A and AB were also more likely to need a type of dialysis that helps the kidneys filter blood without too much pressure on the heart.