Although clinical trials test the treatments that everyone takes, they don’t test those treatments on everyone equally. Despite making up 14% of the population of the United States, less than 3% of all clinical trial participants are Black.1

That small percentage becomes even more disconcerting when you start to consider the disproportionate burden of breast cancer on Black women. Black breast cancer patients have a 41% higher mortality rate than white women as well as the lowest 5-year survival rate of any race or ethnicity.2,3 The relative risk of recurrence for Black breast cancer patients is a staggering 39% higher than for white breast cancer patients.4

These statistics are compounded when you look at Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), a particularly aggressive kind of breast cancer associated with more advanced stages of disease as well as high rates of relapse, metastasis, and mortality.5 Not only do Black women have a three times higher odds of being diagnosed with TNBC,6 they also have a higher incidence overall, which means that there are simply more Black TNBC patients than any other ethnicity or racial group.

Despite the severity of TNBC, only two specific drugs have been approved by the FDA to treat it—one of them is only approved for metastatic patients. TNBC is the only breast cancer subtype that does not have any drugs to prevent recurrence. Of the drugs that are available and FDA approved, none had clinical trial demographics that reflected the actual demographics of TNBC patients. Instead, most TNBC treatments are trialed on white women with early-stage breast cancer who, on average, are 55 years old.7

As is, breast cancer treatments don’t take into consideration the unique biology of Black women. A treatment that works for an older, earlier stage white patient may not work the same for a young Black woman. The truth is, we can’t know without more research and data. In order to test how drugs work on Black bodies and keep Black Breasties (Breasties refers to women who have or have had breast cancer) from dying at higher rates, we need more Black women in clinical trials.

Here’s what the world says about why Black women don’t participate in clinical trials:

In recent years, the breast cancer ecosystem has focused on logistical barriers and social determinants of health as the cause of low clinical trial participation by Black women. These barriers and social determinants include: transportation, financial burdens, access to care, time commitment, narrow exclusion criteria, education levels, geographic distribution of clinical trial sites and site burden, childcare, unpaid time off from work, etc.

In this vein, cancer centers, advocacy organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and research organizations have all rallied around popular interventions such as:

- Gas cards

- Generalized question-prompt lists

- Community outreach via barbershops and beauty salons

- Directing patients to search for trials at clinicaltrials.gov

- Reaching out to Black patients only when actively recruiting for a trial

- Telehealth,

With messaging and language that others (you, your), replicates hyper-clinical rhetoric, and mis-identifies the most critical barriers for Black breast cancer patients:

In many cases, the trial might be for something that is not yet available to the general population of people with an illness. Special allowances are made so doctors can learn more about how well a new approach works… [Clinical trials] could be especially useful if you have a serious illness and have run out of effective standard treatments.

Working with your healthcare provider to gain access to clinical trials is a great starting point. Your doctor may have previously mentioned clinical trials as an option to you.

There are many reasons why so few people, including patients, and fewer diverse patients, participate in clinical trials. For instance, few doctors who see patients also conduct clinical research.

And while interventions to combat tactical barriers and social determinants of health are important, they aren’t the first step. The breast cancer ecosystem has been using these interventions for years, but hasn’t successfully moved the needle for Black breast cancer participation in clinical trials. We need to tackle the nuanced emotional barriers around clinical trials first, before Black women will even consider taking advantage of the interventions listed above. We need to communicate better with Black women via trusted messengers in order to build trust, informed by real fears, earned medical mistrust, and widespread clinical trial misconceptions.

Disrupting the status quo

In early 2021, TOUCH, The Black Breast Cancer Alliance, Breastcancer.org, Morehouse School of Medicine, Ciitizen, Susan G. Komen, and the Center for Healthcare Innovation partnered in order to design our own research that would investigate the emotional barriers to clinical trial participation for Black Breasties under the umbrella of #BlackDataMatters. Starting with Black Breast Cancer, the mission of Black Data Matters is to put patients in a position of power to directly change a research and medical system that often fails Black patients. In this Black Breast Cancer and Barriers to Clinical Trial Research study, we aimed to: uncover and seek to understand awareness, perceptions, and beliefs that drive the genuine emotional barriers to clinical trial participation, assess the unmet needs that must be addressed in order to drive participation in clinical trials, and understand the disconnect from current recruiting tactics, information, and messaging.

We started with qualitative research conducted in April 2021 that included focus groups and individual in-depth interviews among Black women diagnosed with, or at risk for, breast cancer, and their family members. In total, we spoke with 48 Black women.

We quickly learned the most trusted messengers in the breast cancer ecosystem—more than doctors or any other healthcare professionals—are other Black Breasties.

In their own words, here’s what Black women said about why they don’t participate:

- Earned medical mistrust & acknowledgment of past

We need messaging to acknowledge the mistakes of the past and let them know what has been introduced to make sure nothing like that happens in the future.

— Participant, Stage 3C

I think of the Tuskegee experiment, honestly, when I think of clinical trials.

— Participant, Stage 3B

From what we’ve experienced in the past, like the Tuskegee experiments and things such as that, there’s just a rooted fear in the community. — Participant, high-risk group

2. Clinical trials are a last resort

I always looked at it as the last resort like… nothing else is working, that at that point you really wouldn’t have anything to lose so you might as well do a clinical trial.

— Participant, Stage 4

And so I think that kind of last resort, my doctor says, we’ve tried every medication that’s out there. There’s nothing else that’s going to work for you. Do you want to be a part of this trial? That’s the only time when you literally feel, okay, I’m already dying and there’s nothing else that’s going to help me. This is me doing my best to still stay alive. — Participant, high-risk group

3. I’ll be an experiment, a guinea pig

Whenever I would hear clinical trial, I would always think experiment because it was never really broken down to me, I never considered it, and I’ve never been approached personally to participate. — Participant, Stage 2-3

And as far as being a guinea pig and trying something new before they’ve tested it. It’s an experiment to me and I don’t want to be a part of an experiment.

— Participant, high-risk group

I mean, obviously, most people want to find a cure for this, but a lot of people—I’m sure—would be hesitant to put themselves out as the sort of Guinea pig”

— Participant, in remission

4. You’ll get the sugar pill and die

We know in a trial some people get the A, B, and C drug and some people get the A, B, and sugar drug. So I think that’s our biggest fear—I’m doing all of this and then I’m not getting the real deal… Getting the placebo or whatever it is… I mean, the only thing is, and I understand how black people don’t want to do trials, is because I know that to prepare for a trial, it’s a lot of work and it’s very regimented that you have to do all these things. And then just to find out at the end that you didn’t get the actual drug. You know, that’s pretty discouraging. — Participant, Stage 4

But you always get scared. Are you getting the real thing or the sugar pill? And then you don’t know until it’s over that you didn’t get [a real drug]. — Participant, Stage 4

If you do a trial, you’ll get the sugar pill and die! — Participant, Stage 4

5. We aren’t being asked

Give me the opportunity to say yes or no. Ask me and let me say yes or no. I want to be part of the solution. — Participant, Stage 2B

Empowerment. Choice. Options. Opportunity. I want to be the one to make that decision without having someone make the decision for me. — Participant, Stage 3C

I never thought to ask… one wasn’t offered, and I never asked. — Participant, Stage 2A

6. Clinical science feels predatory

They really don’t trust the science and they see a lot of pharmaceutical companies making a lot of money and not coming down to the communities unless they are doing some kind of trial.. they’re just experimenting on us for our information. And then they’re just going to make money from it, sell it to other people to make more money. — Participant, Stage 2 BRCA+

I think we should get recognition, and they shouldn’t try to just take our information. I don’t like the fact that they take our information, and we don’t know if it helps somebody. We don’t get recognition for what we’ve done or compensated for what we’ve done. I just feel like it’s wrong. — Participant, Stage 4

In addition to identifying the key emotional barriers to clinical trial participation, we also sought to understand potential motivators for clinical trial participation. The most impactful was messaging that spoke to participating for fellow Breasties, for future generations, and for the community as a whole. When presented with this lens, Black breast cancer survivors/thrivers responded:

Being a part of history in the making helps reduce the ideas around fear and threat. I’m doing it for myself but also generations of women who have breast cancer. Introduce it in a way that inspires curiosity. — Participant, Stage 3C

It makes you think beyond just yourself, but the value that you’re participating in a clinical trial could give to generations in the future. It speaks to legacy… Your participation could be far-reaching. — Participant, Stage 2-3

And if you participate in the clinical trial, you can possibly help us to gain knowledge about what is triple-negative and the survival rate for African-American women. It could help to go towards finding the positive outcome instead of when you Google and read and you only come up with the negatives. — Participant, Stage 3A

Where do we go from here?

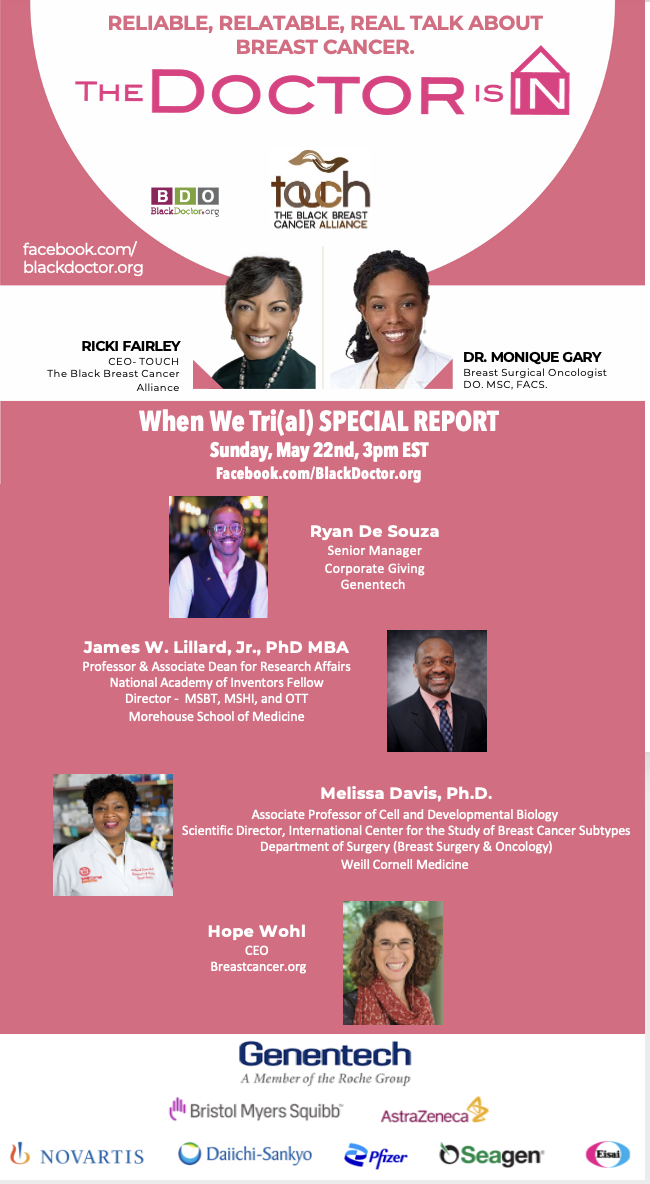

Everything we learned from our research culminated in When We Tri(al), a movement by Black Breasties for Black Breasties dedicated to empowering and educating Black women on the importance of clinical trial participation. Check out the movement at www.whenwetrial.org!

But this qualitative study was just the beginning. We went on to conduct a quantitative research study informed by our rich qualitative learnings. We will publish the results from our quantitative research in late 2022—keep an eye out for our publication announcement on the When We Tri(al) website!

Thank you to the generous partners who sponsored the #BlackDataMatters initiative and When We Tri(al) movement: Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Seagen, and Eisai.

References

1. Schmid P, Adams S, Rugi HS, et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2018; 379:2108-2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615

2 + 3. Cancer Facts and Figures for African Americans 2019-2021. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2019-2021.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed July 21, 2021.

4. Black Women Have Higher Risk of Recurrence Than Other Ethnicities. Oncology Times. 2019; 41(1):24. doi: 10.1097/01.COT.0000552839.22529.72

5. Aysola K, Desai A, Welch C, et al. Triple Negative Breast Cancer – An Overview. Hereditary genetics: current research. 2013;(Suppl 2): 001. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1041.S2-001

6. McCarthy AM, Friebel-Klingner T, Ehsan S, et al. Relationship of established risk factors with breast cancer subtypes. Cancer Med. 2021;10:6456– 6467. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4158

7. 2019 Drug Trials Snapshots Summary Report. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/135337/download. Published 2019. Accessed July 21, 2021.