Every year my mother texts or calls to check whether I’ve completed my annual physical, dental cleaning and vision test. Going to the dentist and optometrist has always been easy to complete, but going to the doctor for routine check-ups and blood tests haven’t been. In my case, accessibility to a network of providers is easy because of the health benefits associated with past and current jobs.

Every year my mother texts or calls to check whether I’ve completed my annual physical, dental cleaning and vision test. Going to the dentist and optometrist has always been easy to complete, but going to the doctor for routine check-ups and blood tests haven’t been. In my case, accessibility to a network of providers is easy because of the health benefits associated with past and current jobs.

With access to such good healthcare, why am I so reticent to regularly go to the doctor?

Why are black men so hesitant to regularly visit their doctors?

I’ve asked myself this question a multitude of times. The answer is layered and nuanced.

There’s a naivety that comes with being young, a black man or both. It’s almost a feeling of invincibility – a false sense of healthiness that’s based off an unprofessional self-assessment consisting of an “I’m okay. I feel good.” If there’s no sharp pain or glaring signs of a problem then there’s no need to go to the doctor. “I know my body” is often our sole justification. Obviously, this is a dangerous way of thinking that positions us to be reactive rather than proactive.

With youth and/or being a black man also comes the blissfulness of ignorance. Being unaware of your current state of health is more soothing than finding out something may actually be wrong. Living in the unknown doesn’t force us to face past actions that may have triggered health issues: whether its sexual activity, substance abuse, diet, etc. Here is when you realize how much we believe in the age-old axiom, “out of sight, out of mind.”

Black men’s subscriptions to flawed notions of masculinity only compound the issue. Our definitions of what it means to be a “real” man are generally shaped by societal and traditional masculine norms, which condition us to be self-reliant and conceal any sort of weakness. Revealing health issues to our closest friends and families puts us in a vulnerable state that jeopardizes our “manhood.” In a sense, black men feel there's a stigma and embarrassment associated with sickness when in actuality it’s just being human in its most rudimentary form.

Another layer we must analyze is black men’s mistrust of the healthcare system. The lack of trust is rooted in racial and prejudice undertones. The relationship between patient and physician is just that – a relationship – and the foundation of trust is broken within the black community. One must look at the historical contexts of blacks and the health care system to truly understand.

Historically, black bodies have been the victim of forced medical and surgical experimentations only to have the results used as justification of their oppression and exploitation.

Dr. J. Corey Williams explained, “In the Antebellum period, blacks were forced to participate in dissections and medical examinations. The psychiatric diagnosis of drapetomania, or “runaway slave syndrome,” was created to diagnose and pathologize African slaves who fled their vicious slave owners. To run away from slavery was considered a disease. The treatment was often amputation of extremities.”

He continued, “Later during Reconstruction Era, white American doctors argued that former slaves would not thrive in a free society because their minds could not cope psychologically with freedom. In the Civil Rights era, psychiatrists used the concept of schizophrenia to portray black activists as violent, hostile, and paranoid because they threatened the racist status quo.”

The infamous Tuskegee Experiment entailed the purposeful injection of hundreds of black men with syphilis and denial of treatment in order to study how the disease affected the human body. With these daunting events in mind, it’s easy to see how the mistrust of the healthcare system was inherited.

Though today’s world is much better, racial prejudice still plays a role in the treatment of blacks in contemporary medicine and public health. Black men are sometimes treated with different medication compared to whites with the same condition. Older medications with worse side effects are prescribed to black men over newer medications with fewer side effects.

Stereotypes of black men lead to longer wait times and doctors’ mistrust of their described symptoms as well. It’s been noted that physicians spend less time with black men as well. Again, the relationship between doctor and patient lacks the empathy and ingenuous nature needed for a patient to feel a particular treatment and prescription is the true solution to a health issue.

On another note, it can’t go without saying that the socioeconomic issues that continue to cripple black communities play a major factor as well. Everything from poor school systems and minimal job opportunities to food deserts and lack of resources accentuate the mistrust as well. The absence of dietary and lifestyle education coupled with a culture of unhealthy eating accentuates the very ailments black men are resistant to addressing with physicians. Adding the reality of jobs without sufficient medical benefits only forces black families to choose between going untreated and expensive medical bills.

The resolution to this generational problem is quite robust, to say the least. It’s not only a change of mindset, but also a change of culture that persists in America. We are more than aware of the systematic oppression and exploitation of black people and a collective effort is needed to alleviate the sickness of mind, body, and spirit on all sides.

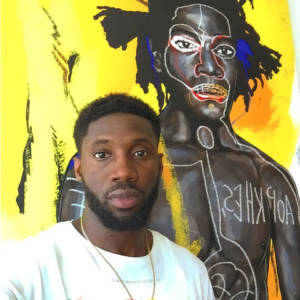

Abdris Elba, B.S. in Advertising – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Ph.D. in Trolling is a SQL/BI developer, aspiring voiceover actor and living proof that the chicken indeed comes before the egg.