60 Minutes recently reported on a gene therapy trial that may be a cure for patients living with the bone-crushing pain of sickle cell disease. Gene therapy locates and fixes the genes responsible for different diseases.

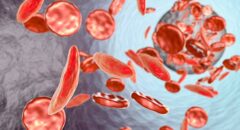

Pain from sickle cell can occur anywhere blood circulates. That's because red blood cells, normally round-shaped, bend into an inflexible sickle shape, causing them to pile up inside blood vessels. The resulting traffic jam prevents the normal delivery of oxygen throughout the body, leading to problems that include bone deterioration, strokes and organ failure.

The gene that causes sickle cell anemia evolved in places like sub-Saharan Africa because it protects people from malaria. There, millions have the disease, and it's estimated more than 50 percent of babies born with it die before the age of five.

In the United States, it affects a hundred thousand people, mostly African-Americans, including sickle cell warrior, Jennelle Stephenson. Jennelle had tried a number of different treatments and had even made the decision to give up being able to have children because of the debilitating disease. But doctors at the National Institutes of Health have discovered another way to attack combat sickle cell.

Here's a partial transcript of the conversation between Dr. Jon Lapook and Jennelle:

DR. JON LAPOOK: I think-- from everything that it looks like, it looks like a cure. And for me, it's especially emotional because from 1976 to 1986 -- ten years when I was seeing a lot of people who had sickle cell anemia. And I could tell you their names still, but I won't for HIPAA reasons. But one after the other, they died.

All you could do was give them pain medicine. So it was a very helpless feeling. So I was taught first, it was, like, the first month of medical school "Someday we're gonna have a cure for sickle cell anemia." That was 1976. And so for me to see that-- that patient, right in front of my eyes, who's cured: Jennelle Stephenson. I didn't know if it was gonna work. Jennelle hadn't gotten any treatment yet. Her whole life she's been a sick person.

JENNELLE STEPHENSON: It's a very sharp, like, stabbing, almost feels like bone-crushing pain.

DR. JON LAPOOK: She thought she was gonna die early. She had a lot of friends who died early.

Then Dr. Lapook went on to describe the risks of gene therapy and that the sheer "newness" of this treatment can make way for so many unknown variables and side effects, including death.

DR. JON LAPOOK: ...No matter how you're doing it-- I mean, you're fiddling with the genes of a human being. Once you put that gene into somebody, you can't un-put that gene into somebody, at least not now. In the future they talk about having a kill switch, so that if things go wrong you can somehow turn the gene off. But that's one of the big fears and there have been real calamities. Death from gene therapy in the past. Well, you talk to Jennelle, she knew all this.

DR. JON LAPOOK: This is fancy genetic tinkering. And it involves putting different kind of genes inside of you that you normally don't have.

JENNELLE STEPHENSON: Right.

DR. JON LAPOOK: Does that give you any pause?

JENNELLE STEPHENSON: I was terrified at first. I think they were using the HIV virus... just because it spreads so well.

DR. JON LAPOOK: Right, a weakened HIV virus.

JENNELLE STEPHENSON: Right. Of course. Of course.

DR. JON LAPOOK: It's amazing. Isn't that amazing. This is a great example of...

... why you have to put money into basic research. Who would have known that figuring out how the HIV virus works would help you probably cure sickle cell anemia someday? We don't know what we're gonna use. We're building up all these tools, we're doing all this basic research. If I someday develop some disease, I'm gonna want a cure for that or a good treatment for it that day. Well, it takes ten, 20, 30 years maybe to come up with that. So, when I see Jennelle, encapsulated in Jennelle and in her success-- is so much.

This clinical trial external link , which is still recruiting participants, is testing a novel gene replacement therapy in people with severe sickle cell disease. Preliminary findings suggest that the approach has an acceptable level of safety and might help patients consistently produce normal red blood cells instead of the sickle-shaped ones that mark this painful, life-threatening disease.

People interested in participating should contact the Office of Patient Recruitment by phone 1-800-411-1222 or email [email protected]