Chad Gradney underwent quadruple bypass open-heart surgery at age 27, and afterward spent eight fruitless years battling extremely high cholesterol levels.

Then in 2012, he found himself back in an emergency room, again suffering from chest pain.

“That’s when I found out three of the four bypasses basically had failed again,” recalls Gradney, now 44 and living in Baton Rouge, La.

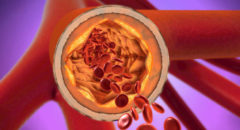

Gradney suffers from familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a common genetic condition that impairs the way the body recycles “bad” LDL cholesterol.

RELATED: Understanding Cholesterol: The “Good” & The “Bad”

How familial hypercholesterolemia affects Blacks

People with FH essentially are born with high cholesterol levels that only increase as they grow older. About 1 in every 250 people inherits the condition, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But Gradney also is Black, and FH tends to be dramatically underdiagnosed and untreated in Black Americans compared to white people, experts say.

Black people are diagnosed with FH at an older age than any other racial or ethnic group in America, according to the nonprofit Family Heart Foundation.

Research also has shown that Black Americans with FH are less likely to have been prescribed cholesterol-lowering medications, even though normal lifestyle modifications aren’t enough to prevent heart disease in someone with the genetic disorder.

“It’s most important to recognize that people with FH are at risk not just because they have an unhealthy lifestyle or diet,” says Dr. Keith Ferdinand, chair of preventive cardiology at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans. “Many of these patients will need not only statins but three to five medications to lower cholesterol.”

RELATED: 7 Ways To Lower Your Cholesterol Every Time You Eat

No one checked for FH

Gradney says no one bothered to check him for FH after his first heart emergency, even though nothing he did afterward seemed to lower his abnormally high cholesterol.

“The doctor wouldn’t blame it on me directly, but it was always something I wasn’t doing,” Gradney adds. “My wife was