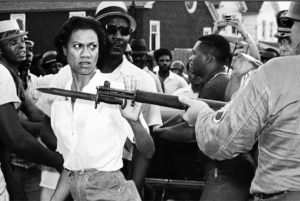

One of the most influential leaders of the Civil Rights movement, Gloria Richardson remains, at 98 years strong, an undeniable figure in not just Black or Civil Rights history, but American history. Some people even call her the "Second Harriet Tubman."

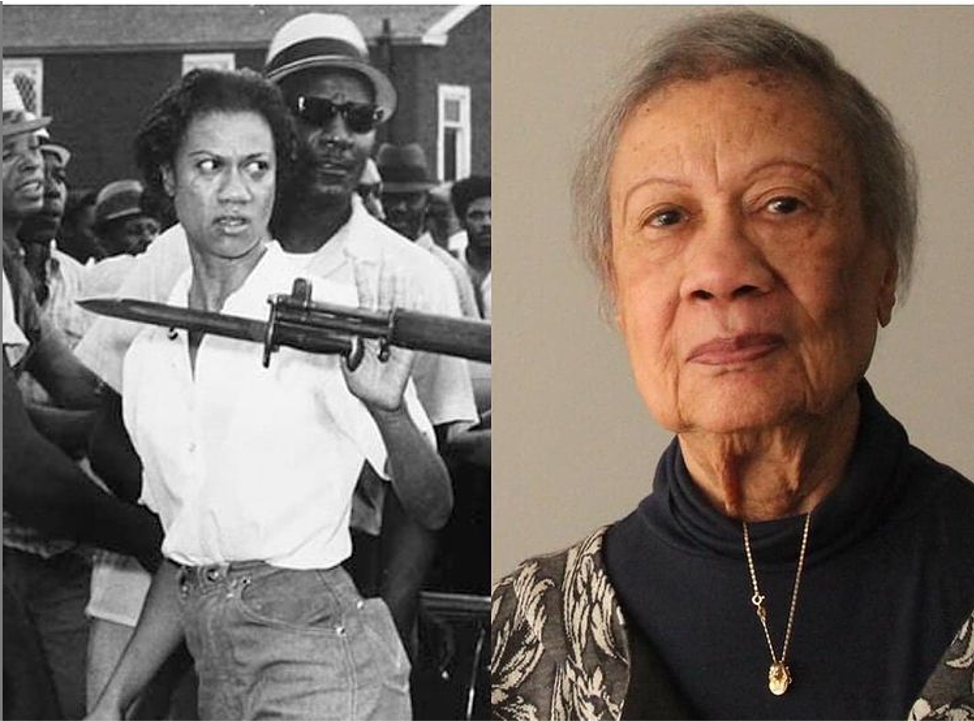

One thing that stands out is the iconic photo of her pushing away a gun and bayonet that showed her stance on not settling for nothing less than the best for her, her community and her people.

According to The Baltimore Sun, Richardson was the first woman in the country to lead a grassroots civil rights organization outside the Deep South. She helped found – and lead – the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC) during a period of civil unrest 50+ years ago caused by racism and lingering segregationist practices.

Her story began in Baltimore during the Depression. Born to John and Mabel Hayes in 1922, Gloria and her family moved to Cambridge Maryland when she was six. Her mother’s family – the St. Clair’s – were prominent and politically active. Gloria’s grandfather – Herbert St. Clair – owned real estate, operated numerous businesses and was the sole African-American member of the City Council.

Gloria left Cambridge at 16 to attend Howard University. She graduated in 1942 with a B.A. in Sociology and worked for the federal government during World War II. When the war ended, she returned to Cambridge. Despite Gloria’s degree and connections, she couldn’t land a job as no agencies would hire a black social worker. Gloria married Harry Richardson, a local school teacher, and was a homemaker for 13 years while raising their children.

Her formal foray into the civil rights movement grew from her daughter Donna’s participation in protests against segregation and racial inequality in Cambridge. Gloria helped form – and was selected to lead – the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee. She was a leader of the Cambridge Movement, a civil rights campaign in her hometown.

Gloria advocated for economic justice; demanding not only desegregation, but also good jobs, housing, schools, and health care. She was an early advocate for the use of violence in self-defense when necessary. In a seminal photo, Gloria is seen pushing away a national guardsman’s rifle after Maryland Governor Millard Tawes enacted martial law.

After 12 African American students were arrested on May 25, 1963, for causing a disturbance while picketing the Board of Education, and two were expelled from school and remanded to correctional schools, Richardson continued the demonstrations and economic boycotts.

Six days later, Richardson appealed to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy for a federal investigation of violations of constitutional rights in Cambridge. She also taught the attorney general an important lesson about poverty and joblessness, reminding him that the civil rights movement was not just about desegregation.

She focused particularly on a segregationists’ effort to put the state’s pending Public Accommodation Law up for a referendum vote the following year, in 1964.

“Many Negroes don’t want to vote on something that already is their right,” Richardson told The Evening Sun at the time. “Public accommodations are a right and cannot be given or taken away with a vote.”

After rioting broke out in June, Gov. J. Millard Tawes imposed martial law on Cambridge and ordered the Maryland National Guard under the command of Gen. George M. Gelston to take charge of the city. Nightly marches that began in the 2nd Ward with the singing of “We Shall Overcome” could be heard as demonstrators headed for Main Street. There, whites lined both sides of the street, pelting them with eggs while calling out racial epithets as Guardsmen stood by.

Led by the efforts of Attorney General Kennedy and other Justice Department officials, a five-point Treaty of Cambridge was agreed to and signed in Kennedy’s office by Cambridge city officials and African American representatives.

After President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the historic Civil Rights Act in July 1964, the National Guard finally withdrew from Cambridge.

Gloria resigned the CNAC in the summer of 1964. Divorced from her first husband, she married photographer Frank Dandridge and moved to New York where she worked for the City’s Department of Aging and National Council for Negro Women.

Gloria still speaks truth to power. A New York resident for 55 years, she continues to inspire people around the world – and in her hometown.

In 2017, the state of Maryland honored her legacy by dedicating February 11 as “Gloria Richardson Day.” Due to an ice-storm in New York, she was not able to travel as planned to Cambridge’s historic Bethel AME to be recognized in person. Thanks to modern technology, she spoke to the packed church in a live remote broadcast from her apartment.