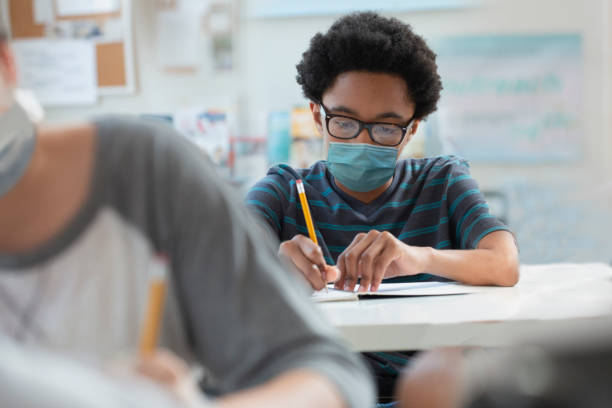

COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations among children are surging across the United States just as students return to school and the highly transmissible Omicron variant begins to dominate the country.

An average of 672 children were being hospitalized every day in the US, as of 2 January, which is double the average of hospitalizations just a week before. The increase in hospitalizations is fueled by the Omicron variant, the holidays, and the pressure on already-strained health systems and schools.

At least nine states have reported record numbers of COVID-related pediatric hospitalizations: They include Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maine, Missouri, Ohio and Pennsylvania, as well as Washington, D.C.

At Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, pediatric hospitalization numbers have surpassed the peak seen during the Delta surge last summer, Dr. Jim Versalovic, co-leader of the hospital’s COVID-19 Command Center, said during a Monday news briefing.

In New York, hospitalizations among kids quadrupled. In Washington DC, children’s hospital admissions have roughly doubled. In Texas, children’s hospitalizations were described as “staggering”. In Alabama, cases were “like a rocket ship”. In Louisiana, one doctor said: “We’ve never seen anything like it.” In Ohio, one associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics critical care recently told ABC news: “We’re on fire.”

RELATED: Could Omicron ‘End the Pandemic?’

“We have staggering numbers here from this Omicron surge already,” Versalovic said during the briefing. “We shattered prior records that were established during the Delta surge in August.”

Ninety percent of the hospital’s cases were shown through sequencing to have been caused by the Omicron variant.

“We have about four times as many children