Some people stand out as trailblazers in medical history, fearlessly removing obstacles and making substantial contributions to the subject. The first Black woman in American history to get a medical degree, Dr. Rebecca Crumpler, is one such extraordinary person. Not only did Dr. Crumpler break glass ceilings with her tenacity, intelligence, and commitment to healing, but she also published a groundbreaking book of medical advice for women and children. This article focuses on exploring the life and outstanding work of Dr. Rebecca Crumpler, MD.

A Trailblazer

Dr. Crumpler's path to getting her medical degree was fraught with difficulty. During an era characterized by racial segregation and restricted chances for women and people of African descent, she rose above the standard and forged new ground. She was hell-bent on helping other people, and that ambition propelled her into a medical profession.

Dr. Crumpler made history in 1864 when she became the first Black woman in America to get a medical degree. Her success was a watershed moment in her career, but it also paved the way for other women of color to pursue medical careers.

A Legacy of Healing

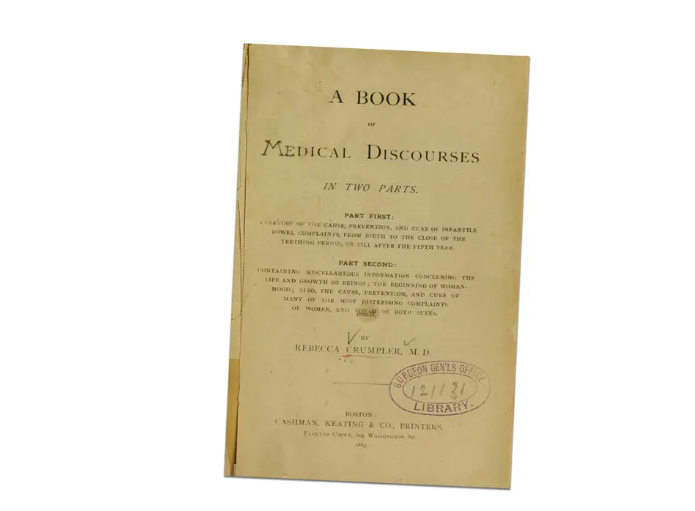

Beyond her professional achievements, Dr. Crumpler's commitment to healing had no bounds. Her groundbreaking work, "A Book of Medical Discourses," published in 1883, offered mothers and children priceless medical counsel. This innovative project demonstrated her dedication to improving healthcare outcomes for underserved populations and highlighted her exceptional medical skills.

"A Book of Medical Discourses" covered various medical issues, including prenatal care, postnatal care, pediatric illnesses, and cleanliness in general. Dr. Crumpler's book became an essential resource for many moms and women dealing with health issues, offering direction and strength.

The Impact of Dr. Crumpler's Achievements

It is impossible to exaggerate the significance of Dr. Crumpler's accomplishments. As a Black woman in medicine, she broke new ground by overcoming long-held prejudices and misconceptions. Aspiring Black women physicians throughout generations looked up to Dr. Crumpler as an example because she overcame cultural obstacles and achieved academic achievement.

Her groundbreaking work in healthcare and her book created the groundwork for modern medicine and patient-centered care. Dr. Crumpler's impact on the medical field is a tribute to the strength that can be achieved with perseverance, commitment, and resolve.

Historical Significance

Her impact on history is immeasurable. Dr. Crumpler broke new ground for women of color in medicine by being the first Black woman to get a medical degree in the U.S. and writing a seminal book on the subject. As her successes demonstrate, a person's willingness to confront the existing quo is often the driving force behind growth and breakthroughs.

Dr. Crumpler's steadfast dedication to healing and her dogged pursuit of making a difference are reflected in her lasting legacy. Her fearlessness in the face of adversity will serve as an example to future generations of doctors and nurses, and her legacy will be one of boundless compassion and scientific inquiry.

Modern-Day Rebecca Crumpler

Former Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders had the same position. Doctor and lecturer Joycelyn Elders was born in Schaal, Arkansas, to Curtis Jones and Haller Reed Jones on August 14, 1933. Elders attended the 1942 Howard County Training School in Tollette, Arkansas. She got a four-year scholarship at Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas, where she earned a B.S. in biology in 1952. Elders received her M.D. in 1960 and M.S. in biochemistry in 1967 from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Pediatric endocrinologist Elders was certified in 1978.

Elders started a pediatric internship at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul after earning her M.D. She became U.A. Medical School's head resident in 1963. Elders joined the University of Arkansas in 1971 as an associate professor and became a professor in 1976. Elders became Arkansas Department of Health director in 1987 under Governor Bill Clinton.

In 1993, Clinton appointed her the 15th Surgeon General. Elders championed public school sex, alcohol, drug, and tobacco education, and women's reproductive health as Surgeon General. After resigning, she returned to the University of Arkansas as a pediatric endocrinology professor in 1994. Elders left the University of Arkansas Medical Center in 2002. The Jocelyn Elders Clinic opened in Kisinga, Uganda, in 2016. The clinic emphasized sex education and treated malaria-afflicted Garama Humanist Secondary School pupils.

Elders wrote approximately 100 research publications on insulin resistance and other endocrine problems. Her book, From Sharecroppers' Daughter to Surgeon General of the United States, was released in 1997.

Elders received the Woman of Distinction Award from Worthen Bank in 1987, Arkansas Democrat Woman of the Year from Statewide Newspaper in 1998, and the Candace Award from National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1991. She entered the Arkansas Women's Hall of Fame in 2016. The National Institute of Health Career Development Award went to Elders. The University of Minnesota Medical School created the Joycelyn Elders Chair in Sexual Health Education in 2009.