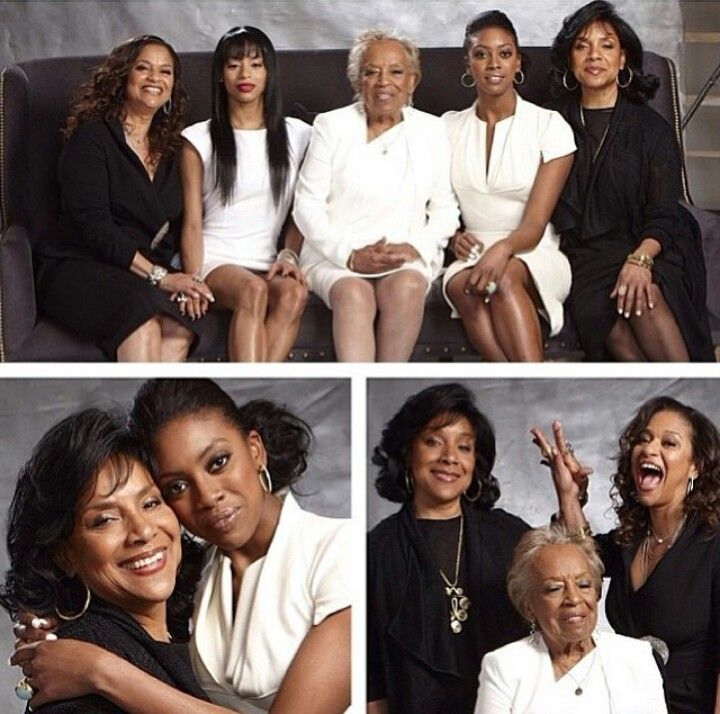

Many of us remember Phylicia Rashad as Claire Huxtable, the wife, lawyer and mother of five, on the long-running, award-winning sitcom, The Cosby Show. We also remember her sister Debbie Allen, the award-winning dancer, choreographer and one of the stars of the hit show, Fame. Both sisters gave us poise, love, and showed us motherhood in a way that was believable and wanted.

But Rashad and Allen say they learned a great deal about motherhood, success and just life in general from their own mother, the poet Dr. Vivian Ayers.

Her literary career began in Houston, Texas with the publication of “Spice of Dawns” (1952), a collection of poems that was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. “Hawk,” an allegory of freedom made analogous to space flight, followed and was published on July 11, 1957, just 11 weeks before the launch of Sputnik I. “Hawk” would later earn praise from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at their Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center where enlarged reproductions of the writings are exhibited.

Dr. Ayers’ talents and interests also include the research of world cultures. She studied classical Greek at Rice University, Columbia University, and Princeton University. In addition, she has studied and translated texts on Mayan culture and astronomy.

In 1973, while still living in Houston, Texas and working with the Harris County Community Association, she collaborated with certified teachers to create her signature program, “Workshops in Open Fields.” This method of education was recommended to the nation as the prototype of grassroots arts programming.

Vivien also had a knack for crunching numbers and was the real-life "hidden figure." She used to work at the Johnson Space Center as a mathematician in the 1960s.

"It was my mother who taught us choral speech," Allen shared. "It was my mother who taught us to tumble across the living room floor. It was my mother who gave us a real appreciation for art and literature as living things, not just as something hung on the wall or placed on the shelf — an appreciation for ideas and the power of thought and human intention. My mother gave us a lot — she gave us everything."

Off-screen, Phylicia Rashad was forging her own way into motherhood and took some lessons her own mother gave her along the way.

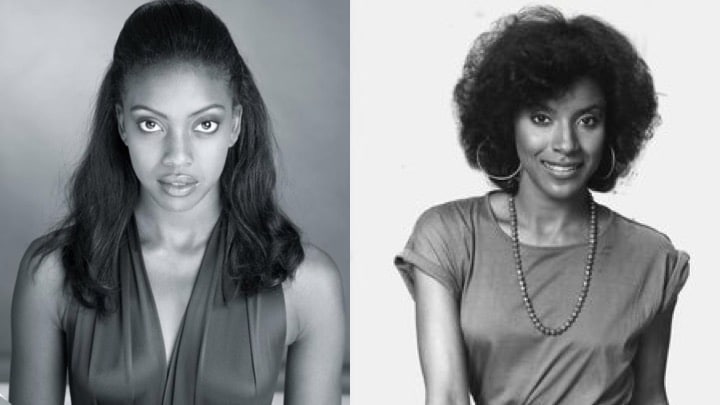

Phylicia’s real-life daughter, Condola Rashad never minded sharing her mother with the world.”It feels just like anyone else and their mothers, it’s no different. I’ve never known any other mother,” Condola explains of growing up with Claire Huxtable as her mother.

TAKE A LOOK BACK: Phylicia Rashad Writes A Letter To Her 21-Year-Old Self

Condola was one of the few black people of the world that grew up not watching “The Cosby Show” because she spent her every waking moment on set. As a real-life "Rudy," she learned the ins and outs of acting and decided that she would follow in her mother’s footsteps.

Broadway welcomed Condola with open arms after her many appearances on the big and small screen. It was her performance in “Stick Fly” that gained her a Tony nomination and garnered national attention. In the remake or “Steel Magnolias,” Condola starred as Shelby, alongside her mother and was praised for her performance.

Although she grew up on the set of ‘the Cosby Show’ and was always around backstage during her mother’s work day, she says she felt fortunate that she wasn’t treated any differently than any other ‘normal’ kid during her childhood. But, she made sure to mention that she, indeed, rebelled, but much later than most children as she did so during her college years.

"My daughter says, 'We have to be careful with the roles that you play,' " Rashad says. "I asked why, and she said, 'Cause you always bring a little of that home.'"

Rashad recalls that when she was performing Medea more than 10 years ago, she snapped at her daughter.

"My daughter was quite young, and she had come backstage and she was doing what children do and got a little splinter in her finger just at the moment that places was called," Rashad says. "And she came running to me, and I turned to her and said, 'I can't deal with it right now!' And I never talk to my daughter that way. And her eyes got so big. And I said, 'I'm sorry, I really have to go.' And then I called someone else to come assist her, and it was taken care of. But she said, 'I don't know if I like that lady.'"

"As a child, it was amazing to have my mother — and somewhat disconcerting at times, because she wasn't like other mothers," Condola says. "Other mothers didn't get up at 3 o'clock in the morning to write. My mother did, every day."

Condola says she'll never forget when...

she was only 6 years old, around Easter, her mother called the neighborhood kids into the house and taught them musical notes using candied Easter eggs.

"She wrote it out for us to see what it looked like on the staff," Rashad says. "She said, 'Four beats to a measure and a quarter-note gets one beat. Now what is a quarter-note?' Well she held up an egg, she said, 'Well, this is a whole Easter egg, we're going to call this a whole note. And in 4-4 time, the whole note is getting four beats.' She proceeded to divide that Easter egg into 16 parts.

"And I didn't understand it at the time, but I was learning fractions — and I never forgot it. I never forget the concept, the principle behind fractions."

At 99, Vivian still tutors young children at the Brainerd Institute Heritage, which carries on the mission of an elite black boarding school that closed in 1939.

With her daughters, Vivian bought the land on which the school stood and revived the institute.

For this clan of women who refuse to slow down, there is no such thing as an impossible dream.