GPS or the Global Positioning System is something that we use every day. From finding your local supermarket, checking your directions if you get lost or mapping out your daily commute to avoid traffic, GPS is with us everywhere we go. It has literally changed the way we work, play and live.

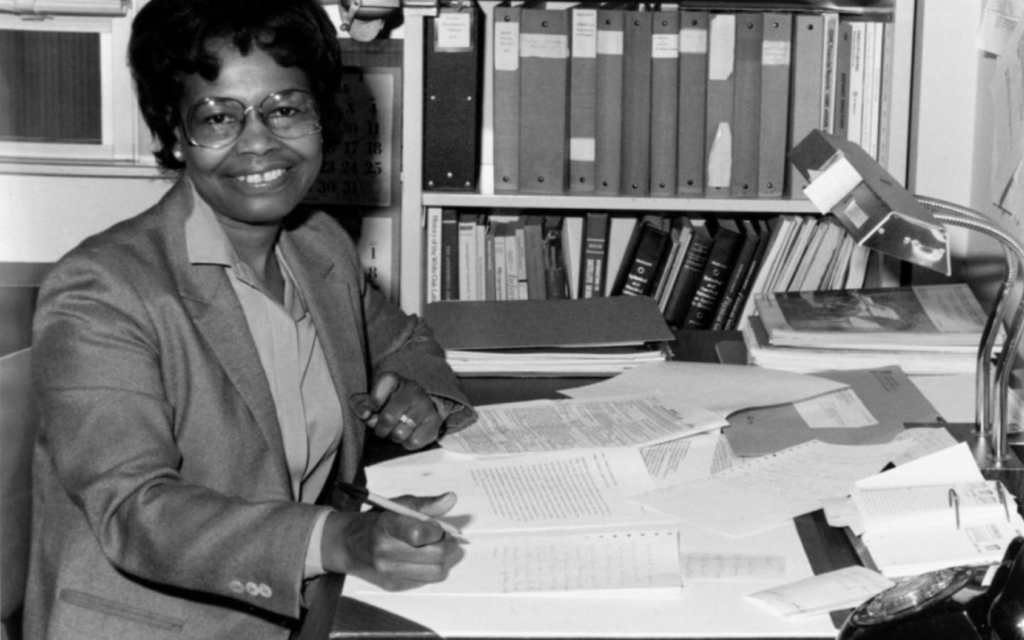

While billions of people use GPS in their car or on their phone, many don't know that a Black woman is behind the creation of it. That's right, Dr. Gladys West, a Black woman from Virginia was instrumental in creating the device we use today.

And now, she's finally getting her recognition that's long overdue.

In 2018, the now 91-year-old West was inducted into the Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame by the United States Air Force during a ceremony at the Pentagon.

As a girl growing up in Dinwiddie County south of Richmond in the late 1930's early 1940's, all Gladys (maiden name, Brown) knew was that she didn’t want to work in the fields, picking tobacco, corn and cotton, or in a nearby factory, beating tobacco leaves into pieces small enough for cigarettes and pipes, as her parents did.

“I realized I had to get an education to get out,” she said.

When she learned that the valedictorian and salutatorian from her high school would earn a scholarship to Virginia State College (now University), she studied hard and graduated at the top of her class.

She got her free ticket to college, majored in math and taught two years in Sussex County before she went back to school for her master’s degree.

In 1956 West began to work at Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division, where she was the second black woman ever to be employed. West began to collect data from satellites, eventually leading to the development of Global Positioning System. Her supervisor Ralph Neiman recommended her as project manager for the Seasat radar altimetry project, the first satellite that could remotely sense oceans. In 1979, Neiman recommended West for commendation. West was a programmer in the Dahlgren Division for large-scale computers and a project manager for data-processing systems used in the analysis of satellite data.

In 1986, West published "Data Processing System Specifications for the Geosat Satellite Radar Altimeter", a 60-page illustrated guide. The Naval Surface Weapons Center (NSWC) guide was published to explain how to increase the accuracy of the estimation of "geoid heights and vertical deflection", topics of satellite geodesy. This was achieved by processing the data created from the radio altimeter on the Geosat satellite which went into orbit on 12 March 1984. She worked at Dahlgren for 42 years, retiring in 1998. Her contributions to GPS were only uncovered when a member of West's sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, read a short biography West had submitted for an alumni function.

West's humble nature actually kept people from knowing how instrumental she was in the development of the device for decades. West admits that she had no idea, at the time, when she was recording satellite locations and doing accompanying calculations—that her work would affect so many.

“When you’re working every day, you’re not thinking, ‘What impact is this going to have on the world?’ You’re thinking, ‘I’ve got to get this right,’” she says.

And get it right she did, according to...

... those who worked with her or heard about her.

Ralph Neiman, her department head in 1979, acknowledged those skills in a commendation he recommended for West, project manager for the Seasat radar altimetry project. Launched in 1978, Seasat was the first satellite designed for remote sensing of oceans with synthetic aperture radar.

In a 2017 message about Black History Month, Capt. Godfrey Weekes, then-commanding officer at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division, described the “integral role” played by West.

“She rose through the ranks, worked on the satellite geodesy [science that measures the size and shape of Earth] and contributed to the accuracy of GPS and the measurement of satellite data,” he wrote. “As Gladys West started her career as a mathematician at Dahlgren in 1956, she likely had no idea that her work would impact the world for decades to come.”

“I was ecstatic,” she said. “I was able to come from Dinwiddie County and be able to work with some of the greatest scientists working on these projects.”