When Darlene Anita Scott started experiencing shortness of breath at age 41, her first worry was how it would affect her running.

In her 20s, she was a frequent gym-goer who loved spin classes. Running arrived in her 30s after Scott, a poet and creative writing teacher, moved to Richmond, Virginia, for work.

On one of her daily 4-milers, she passed a group of runners with the River City Runners of Color. They invited her to join them.

“They were training for a half-marathon, and I didn’t even know what a half-marathon was,” she says.

On her first outing with the group, she was so busy chatting that she ended up going 8 miles. Soon, she wanted to not only run a half-marathon, but a full marathon – 26.2 miles. She got so into running that her schedule and social life revolved around it. Her diet did, too, as she became vegan and eschewed processed foods.

RELATED: 5 Heart Failure Symptoms Doctors Commonly Miss

“I was not just healthy, I was optimally healthy,” she shares.

In spring 2016, Scott was teaching full-time at a university and had taken on a chair position. She was also training for her eighth marathon, one she hoped would qualify her to compete in the Boston Marathon.

With all that going on, when her breathing began to feel labored, she figured she was just overdoing it. She started going to bed earlier and earlier, but it didn’t solve her problem.

Her general practitioner thought the problem might be exercise-induced asthma. She referred Scott to a pulmonologist.

When lung function tests showed no problem, chest X-rays were ordered. The test showed an enlarged heart. She went to a cardiologist’s office, where she had an echocardiogram.

“Your heart is not pumping like it should,” the cardiologist said. “You’re in heart failure. It’s amazing that you’re running at all.”

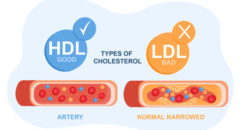

Her ejection fraction was at 20%, meaning 80% of her blood stayed in the heart’s ventricle instead of pumping through her body.